[Check out Part I. — Picking up from 47:09]

David Kane: I just wanna say that I love the opening of this movie, because I love dystopian propaganda as an aesthetic.

Shockaholic: (laughs) It’s very good.

DK: It’s the perfect paradox of, “You should feel fine,” and as a viewer, you’re like, “I’m gonna go with Not Fine. I’m getting the idea that should not feel fine, and you’re trying to calm me down.” That’s another thing about Horror that I forgot to say, where I feel a kinship with the audience that I’m watching with because we’re all agreeing this is fucked up, what we’re watching.

S: Right.

DK: When I was a kid, one of my most powerful nightmares was, “I’m in danger, but nobody thinks I am. And I can’t communicate that I’m in danger.” Very A Nightmare On Elm Street, y’know, very Kid Horror, Teen Horror. But it’s universally applicable, and I feel calmed when I watch Horror movies that go, “Yeah, you’re in danger, this character is in danger. You can see it. And you’re gonna watch them survive this or not.” That’s part of the excitement.

S: (laughs)

DK: I feel such powerful kinship with the Horror community because we all go, “Yeah, something is wrong. There is danger.” We’re all going to share in the sensation of feeling afraid. But being safe.

S: Yes. I think that Horror works like a sort of emotional and sensational survival guide. So not necessarily the practical skills. I know for some people it has. I’ve seen people say they love slashers for the fact, y’know, that they have been able to learn from the folly of the characters that are involved. But if you look at Horror just in the wide scope of the types of the genres and stories that you can get. As you were saying, the very first response we have, as sentient creatures– Not even as human beings, just as being alive– is sensation. We have an experience and then we respond to this experience. We however don’t come with some sort of preloaded knowledge of the universe and history whenever we’re born. We have the evolutionary stuff, of course. We know naturally how to swim and things like this, if you are put into these situations at a young enough age. But we don’t have the same social understanding or historical context, so we have to relearn these things. Every generation has to learn these things. And I think Horror is amazing to teach this through the different types of showing that danger. Y’know, the ways that we see people struggle and fail, we don’t have to fail then. We can see where the failures are. And let’s be honest, most of the time it’s communication where the failure lies in most Horror films. This is a massive exception to that. But that’s because this film takes place in a more metaphysical Horror sense. In a way I would say this a more frightening film than most of your monster movies or slasher or anything that’s like a direct– For instance, the ending of the film is probably the least frightening moment for me. The last maybe twenty minutes or so. Because for one it’s more an adventure, like kid-adventure of Elena escaping the compound. Y’know we’re getting our E.T. moment, basically. And then it turns into a slasher with Barry going on, y’know, a killing spree. But before all that, Barry scares me to the fullest extent because he is an ethereal cosmic entity basically. He is human existence that is distorted. And that freaks me out way more.

DK: And I love that this movie operates on multiple levels, where he represents evil in the universe, but he is also just a dangerous man. He is a dangerous man, and we haven’t brought it up: he has sexual designs on Elena.

S: Woof. Yes.

DK: And he’s a man in power taking advantage of his power for a helpless teenager. If you do the math, she’s between sixteen and eighteen. And it’s unambiguous that he sees her that way. And that’s terrifying in reality. That version of him is grounded in everyone’s experience of real reality. But on top of it, she’s got superpowers and he might be a demon. So… (chuckles) And it works! It’s very parable like that, while still being like, the danger is real. And he goes from a doctor who’s like, “I’m a mad genius,” to “actually, I’m a lunatic. You can’t trust what I’m going to do.” He changes from moment to moment in certain scenes, where he’s, like scary and on top of it, but then he’ll be– Like when Rosemary catches him doing his transformation–

S: Yeah!

DK: –he’s acting like a kid who wet the bed.

S: And then he lashes out.

DK: And he goes from vulnerable and saying, “I’m not okay” to “I’m gonna murder you!”

S: Wait, wait, to “I am a part of The Divine, and I’m going to murder you.” His ego just thrusts forward right before he kills her. It’s quite intense how quickly he snaps back to “I am a perfect being.”

DK: Yeah, and what I love is that the sci-fi element of the movie is declared early on. Elena’s powers are real. She’s got ESP, she can blow up brains. That’s the sci-fi reality we live in. And then as we learn of Barry’s backstory, he goes on this trip. And what’s funny is we see a drop go on his lip. “LSD” is never said in the movie, but because we know history, we’re like “That’s acid.”

S: Mhmm.

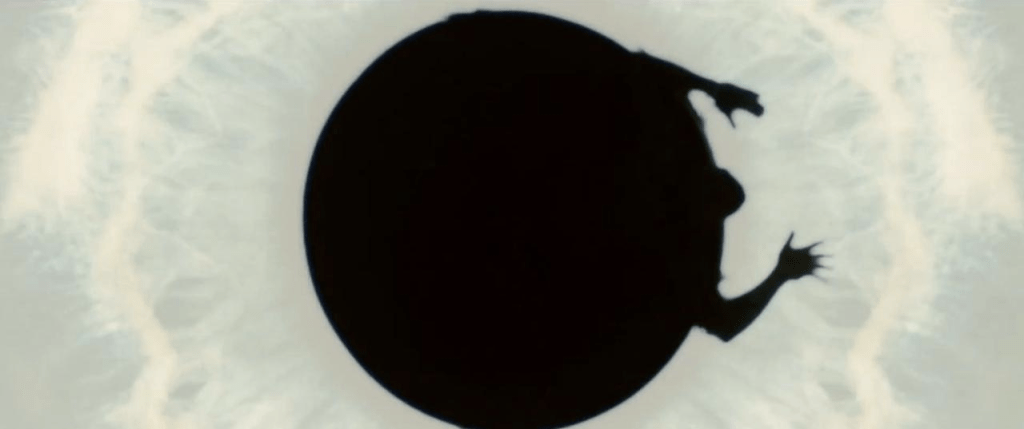

DK: That’s part of our participation in the movie of like, y’know, every synopsis calls it a drug trip or an acid trip. And the movie doesn’t say that, you’re saying that because you know its referring to that. He has this incredibly abstract experience within the pit, and he comes out a lunatic. And years later claims to have been confronted by something that was “like a black rainbow.” The god– in the subtitles it’s “the eye of the god.” Which is more mysterious than just saying the eye of God.

S: Right.

DK: And what I like is that the veracity of that experience is questionable. When I first watched the movie, I was like “he’s just a madman.” But then I watched it a second and third time, I was like, “is the black rainbow real?” Superpowers are real.

S: Yeah. It could be.

DK: I like that the movie withholds that. The viewer finds him scary on any level that they think is the scariest.

S: Mhm.

DK: At the bare minimum, he’s a dangerous man wielding a knife who has sexual drawings in a cabinet. (laughs) And then beyond that, he claims to have seen God who gave him permission to kill people. And because this movie-world is mutants and superpowers, he might be right. And the fact that the movie doesn’t show you too much. You don’t see the black rainbow at work in a way that like– he could be nuts or he could be right. And the fact that they don’t clarify is spookier.

S: Yeah, and there are also little hints to it being a kinda cosmic event that’s taking place too. I mean, the fact that Elena, when she leaves and looks out into the sky, one of the first things she’s sees in the stars is a nebula and all these different cosmic structures. It could be seen as a metaphorical thing. It could be that she has such a heightened senses, she can see things for how they really are. But the fact of the matter is, there’s still this connection between the universe, existence, and whatever situation is taking place in this reality. Whether it is based on drugs or based on an actual spiritual enlightenment or event that Barry is going through. I was reading up on some quotes for this episode that I– every episode, I always like to look through the filmmaker’s quotes just to see if they have something that I find like, “This is it. This is better than philosophy. I wanna bring this in.” And I struggled a little bit about Beauty specifically, but I did reach some stuff that Cosmatos was saying. That his films, and specifically this one, or actually both of them. Both of the films that he’s made, this and Mandy, are about when you have men that are in positions of power that they have created for themselves. When they are questioned or shown the reality of the situation– that in reality they don’t actually have that much sway or power– the downward spiral that they go through and how they become monsters and lash out because they are emotionally incapable or ill-equipped to accept their own mortality and their own averageness basically.

DK: Smallness.

S: That kinda fragile ego.

DK: I’m really happy that you brought that up. ‘Cause I do think that he makes movies about– the villains are small men who feel big. And part of Barry’s transformation, which is like— Yeah, Jeremiah Sand in Mandy and Barry are related. I mean as characters, and their origin stories are very similar. Where they both saw God, who gave them permission to be evil. And then they feel entitled to the bodies of women. That’s also a common thing. And you don’t think they’re cool. They think they’re cool, and they’re so ridiculous and small. As a man, I enjoyed watching that. I enjoy that these movies feel like takedowns of toxic patriarchy. I enjoyed seeing Barry go from, like “Yeah I’m God,” to “I broke my neck because I tripped.” (laughs)

S: I was mad at first. I’ll explain first why I was a little upset with it, and then I’ll explain why I love it so much. So the reason I was at first a little upset was just that, I think Elena’s kind of an afterthought in this film. That for such a powerful creature– I say creature not to be diminutive to a woman–

DK: She’s a mutant. She’s like an X-man.

S: Well, I also just mean like how humans are also creatures. Like a creature of existence. Of the universe. Y’know, to be so powerful and to put it in those terms. To be this powerful mutant, who isn’t really explored in the lengths to which what she can do. She’s kind of a Jean Grey figure there. It’s like what can you actually accomplish if you were to just unleash your full power? I was a little like, y’know, this guy’s been in your way you’re whole life. And you didn’t even get to do anything. You were just standing there scared. And then this dumbass just trips on a piece of stick and then breaks his neck on a rock. At first, I was like “No! This is not satisfying at all.” But then I thought about it more, like this is so satisfying because he thought he was so overly powerful and godlike, and he couldn’t even walk. Like it was gravity that ended up killing him. A force that was stronger than him, that he didn’t respect.

DK: And his last words are demanding that she come to him, and because she refuses you can see him cracking. Which is the same moment in Mandy. Mandy is a very similar character where she doesn’t have a lot of power because the man in power is asserting his power. The villain is asserting himself. And she uses her agency to refuse, and that’s a capital crime. The thing about Elena is she’s like a mythological figure of innocence. She was born here. She’s had no chance to form her personality.

S: True.

DK: That’s her struggle, “I need to get out of here because I can’t learn who I am in this simulated reality. I have to escape to myself.” And we don’t get to see who she becomes. And she’s not– She doesn’t take pleasure in this death– Never mind, she giggles at his death.

S: She does smile, yeah.

DK: But she doesn’t take revenge. That’s the other thing is, y’know, in Mandy Red takes revenge. Which is a brutal act, and that movie is about how revenge itself is kind of evil. And you have to become a little evil in order to take revenge. Because it’s brutal and it’s violent. And he does it on behalf of the figure of innocence. The “good person.” And Elena– When I first watched it, I thought she was using her power to stop him. And I think it’s pretty explicit: his foot is stuck. But I think she would– She’s afraid of him, but she could use her power to do anything. And you see she makes the choice of no. “I’m refusing the command you’ve given me. You’ve been commanding me all of my existence. You’ve been commanding my body with your evil crystal. And now that I’m free, all that I can do is say no.”

S: Important note. It’s not just her body, it’s her body and her mind. Spirit. Everything that he’s tried to control. So that is actually quite beautiful in itself. That in this moment she decides to not use her powers, because he’s fetishized her power, his whole– Well at least her whole–

DK: Her entire life. She was born in a cult.

S: Yeah. But I also mean this kinda erotic drive that he has. You see how he– it’s almost orgasmic for him when she tries to use her power against him. ‘Cause he feels like he’s touching something divine and enlightening. And something that spiritually only he would understand ’cause only he has the wisdom to do that. So “hahaha little girl, you don’t know what you’re even trying to do. And I can control that.” So I did love that she let him be his literal downfall. There at the end of the film. It’s his own hubris that causes it.

DK: Yeah, and that’s the thing. He is an abuser– these villains are abusers– who takes pleasure in her attempts to fight back. And just portraying that. But it’s truly like, when his ego is truly wounded– Also, he’s on her turf. She’s spent her entire life within Arboria, and he’s controlled that reality. And now that she’s in nature, he’s out of his element. And you could say that he’s not used to walking around branches and trees. And he’s wearing his little boots.

S: (giggles) His cute little boots.

DK: Yeah, and I have a question that I wanna ask you.

S: Okay.

DK: You remember the scene when he’s driving after her. And he turns, and he sees a vision of his old self sitting in the passenger seat. What does the vision say?

S: He says, “You’re doing good.” I caught myself correcting him, “you’re doing well.” You’re a scientist, you should know better. But then I thought of it, and like, no, you’re putting a moral imperative on what you’re saying here. You’re doing good.

DK: Yeah, I think that’s the black rainbow. Or the essence of the black rainbow.

S: His god basically.

DK: Because he’s driven by ego, it’s himself that’s appearing. But when I first watched this I thought I heard him say, “You look so good.”

S: (laughs) I can see that.

DK: My DVD doesn’t have subtitles. I had to watch a different version that had subtitles in order to confirm, like “okay, I’m not wrong.” And when I told another friend about it, we talked about that moment. And my friend said, “Yeah he said ‘you look so good.’” So we both misheard it, and this is an example of like people experiencing the movie differently and coming to different conclusions that still fit. And the correction takes the analysis into a different direction, but he’s so ego-driven that “you look so good,” is kinda the same thing as “you’re doing so good.” Especially because he’s finally taken his wig off. He’s finally put his spooky clothes on. His custom leather. And he’s holding his dagger, which is another great mystery of the movie. Also you might have recognized that they recreate that moment at the end of Mandy.

S: It’s been a while since I’ve seen Mandy, but now I’m gonna look out for it when I watch it.

DK: Red has completed his crusade, as he’s driving away he turns and Mandy is sitting next to him.

S: Ah. Yeah, okay. yeah.

DK: And she doesn’t say anything, but she looks at him. And the reverse-shot is him smiling, and then he turns back. Shot for shot. They’re the same scene in Black Rainbow and Mandy.

S: That’s powerful.

DK: And Mandy doesn’t say anything, and I remember thinking, “Did they cut her saying the same thing Barry said?” ‘Cause she communicates the exact same sentiment, but it’s romantic. For Barry, it’s evil. And in Mandy, it’s romantic. I think it’s incredible. You’re seeing their dark passenger, who’s driving them.

S: Yeah. Which says a lot about idealization as well. If you compare the two films. The whole drive for Red is a sort of idealization of Mandy. He sees her as something pure, and something that is perfect and gentle and good. But she’s a person. She’s complex and has her own agency and wrongdoings like any other person. She’s not perfect, that’s the whole Beauty and perfection of humans, is we’re not perfect. So this touches upon something I love about Cosmatos’ films. A lot of filmmakers, especially male filmmakers, would get criticism for having characters that are female but passive. And I was a bit critical of that at first as well, but then I realized like, ah, but normally it’s because the film tries to make it about the women. As if this is our hero, this is who you should be focused on. And then you get a kind of cookie-cutter cardboard no-character because a man wrote it and doesn’t even understand how to write a woman. In this case, this isn’t what these films are about. These films are more about dissecting the ugly sides of masculinity.

DK: Yeah.

S: In Mandy, you have it on two notes. So like, if Beyond the Black Rainbow is the start of this conversation by showing it purely through your villains– the two different kinds of toxicity you can see in masculinity– Mandy shows it again with the cultists. But then with Red himself you also see this kinda chivalrous masculinity that is both positive and negative at the same time because of how he idolizes and has this strong perfect view of his partner. When it’s still like, “but are you still seeing her for her? Y’know, are you seeing her image of her? Or are you seeing her for her?”

DK: And he’s a heavy metal demigod. So you’re going to get– Who’s committing acts of violence. That’s what I love about Mandy is that it’s like, “I’m off the edge now. The love of my life is gone. I have been consumed by darkness, and I’m not leaving this world until I’ve cleansed the evil from this world, which requires me to descend into Hell.”

S: Yes. And become one of them.

DK: Yeah. And the reverse of like– I’ve got fan theories about the connections between the cult and Arboria. But The Black Rainbow is about a man becoming a monster and leaving this lair, and Mandy is about a man who becomes a monster and then enters the lair of the devil.

S: Yeah.

DK: In Mandy— here’s my fan theory– when they stab Red before the burning, Brother Swann says, “This is the tainted blade of the pale knight, straight from the abyssal lair.” I think he’s talking about The Devil’s Teardrop.

S: Could be.

DK: And that, like, when I first watched it, I was like “that’s just nonsense, crazy-person talk for a villain.” But after watching both movies again, I was like: Oh shit, there are connections that don’t really matter but I’m finding them. And that’s me– I’ve become a crazy cultist for these movies. But we’re getting sidetracked. We have to talk about Black Rainbow. But I like that Barry is, it’s a male filmmaker making a movie about an evil man.

S: Exactly.

DK: And digging into him. As a male viewer, I appreciate that. ‘Cause this genre is full of men attacking women, and so many books have been written analyzing that aspect of it. And I feel like we’re now approaching a moment in history where we are turning our lens back and making movies that approach these dynamics. Especially because the thing that– the element that ties this genre together is violence. This movie is going to have violence in it. Even spooky hauntings have these moments of violence. It’s just what kind of intensity? How much gore? But someone gets hurt in Horror, and we feel horrified for them.

S: Yes.

DK: And I like that the violence in these Cosmatos movies are men against– or they want to hurt women. And that’s what is horrifying about them. I like seeing that being like, “Yeah, let’s point out how that’s a bad thing.”

S: Yes. And I love that from the very get-go, by setting it here and showing the footage of Reagan and stuff, you’re also showing a kind of origin for, not like a pure origin, but a modern-day origin for like the resurgence of this being a norm. It came a lot from Reaganomics and the trickle-down idea for the elite, when the elite were all just privileged white men of course. Then you’re only gonna live in their viewpoint. And the film itself mirrors this really well and shows this really well, because you have characters like Margo and Rosemary. Okay, so we have other women who do nothing to help this small girl. And in Margo’s case, we don’t know much about her, but we see her just kinda doing her job. She’s so shitty to Elena. And she’s only really shitty to Elena when she’s been treated like crap by Barry. And it shows how these power-plays, the trickle-down effect, if you will. The toxicity just sprays on other people. And regardless of gender identity, ethnic backward, social dynamic, we all become lesser when we engage in this world. Because we are either put down by the power-system, or we are on top and trying to stay there. Look at Rosemary. Question for you: what’s your interpretation of her? Is that his mother? Sister? What is the relationship here?

DK: Exactly! That’s another example of like, whatever conclusion you come to, I have to be like, they never say it. The only thing you know is they have the same last name in the credits. And you never see their bed. You never see a bedroom.

S: She sleeps on the couch.

DK: Yeah, sleeps all day on the couch.

S: And she’s a little older.

DK: You don’t know Barry’s age! Because in the flashback he’s all washed out, and his makeup looks bad. He’s meant to look younger. And that’s the thing– I’m so happy that you brought that up. ‘Cause Rosemary’s just some family member. And however you want to read it is how you’re gonna read it. I think because Rosemary is Timothy Leary’s third wife, she’s Barry’s wife. But I like placing her as just this woman who cares about him. Who’s related to him in some way. And I think everyone in the movie used to be, like on equal footing in the formation of the commune. Because it was this ’60s hippy-commune-turned-cult, where everyone was told they were equal, but then male egos get put at the forefront. And I think that she was at some point, because also on the table is a book by Arboria that’s full of notes. So I think she was probably one of the healers that is mentioned as one of the founders.

S: Mmm.

DK: But just like Mercurio being just drugged up in a basement, she is just getting high on the couch, saying she’s meditating. ‘Cause you also see some stuff on the table. What looks like it could be hashish or weed or something.

S: Some ashes of some kind.

DK: And I think, ’cause the whole lesson of the movie is everyone is on drugs– and that’s bad–

S: (laughs)

DK: I think that she’s checked out. The big traumatic incident that happened a long time ago was, the founder’s wife was killed. And it’s Barry who did it. So she probably has no way to process it, ’cause she can’t leave. And it’s been years, and no’s getting any better. So she’s just going to check out. And she cares about Barry but can’t care enough. Because he’s truly evil. And her death is a sad, sweet moment, where she says, “I should’ve been there for you more.” She finally recognizes that like– And what’s weird about it is that he’s the monster. She recognizes that he’s been hurt by the violence– that the system of violence is hurting everyone.

S: Yes!

DK: And you mentioned Margo being an underling, but because she’s over someone else, she takes advantage of her power. Which is Kafkaesque. A big thing in Kafka is, you never see who’s in charge. Violence is in charge.

S: Yup.

DK: One of the influences [Cosmatos] stated for the writing of the movie was William Burroughs, the beat poet.

S: Okay.

DK: The pills he [Barry] takes are from Benway’s pharmacy. Benway is a villainous psychotic doctor in Naked Lunch.

S: Oh crap, okay! That’s a great reference.

DK: Yup! And… I love it. He [Burroughs] has a lot– He wrote a whole essay on Control, and he said it’s not just violence; those in power use language to control. And that makes me think about Dr. Mercurio saying like, “sensory therapy and energy sculpting.” Which is a nonsense term! And you the patient are like, “okay I’ll trust– You’re saying a bunch of words I don’t understand, but you’re a doctor, so I’ll trust you.” And that’s the first mistake. But there’s a big quote of [Burroughs] that’s like, “There’s no practical end result for Control. Control is only used as means for more Control. Like junk.”

S: Exactly.

DK: And he wrote a lot about addiction being an ecosystem. That the junky sees their body as a vessel for the drug. The drug is way more important than their own body. They objectify themselves within the act. And I like– Mercurio being a junky in the basement is absolutely also a reference to that. This society is addicted to Control for no reason. And Barry’s at the top, and he hates it.

S: You’ve just made me build a little bit of a theory here about the film, based on this reading of addiction and power-systems. Because on one hand, Barry on paper is in control. And physical he’s in control. But as you were saying, was it a quote from Burroughs about language being a way that–?

DK: Yup, yes, he wrote an essay about language being a virus [from outer space]. But yeah it’s his.

S: Okay. That you see in the film in many ways. You see it in how Barry mumbles. So he just kinda expects people to understand him. You see it in, as I’ve already mentioned, how Dr. Arboria will not be referred to as Mercurio. He will not allow him– He just shows the power-play by being like, “I’m asleep until you use the right language.” There’s also something we haven’t touched upon, which are the videos that they show to whoever is in captivity. So this is something– like Dr. Arboria isn’t even aware of the fact that he’s in captivity, even though they’re showing him the same indoctrination videos that they’re showing Elena. To kinda coax you and relax you. And kinda treating you like you’re in some sort of resort in Florida. Like, “look at all the palm trees. A documentary about the ocean.” And these fun– “the getaway and the beach.” What I find very interesting though, is that Arboria just sits back and watches it, ’cause like he says, “Ah it reminds me of a simpler time.” So he’s actually succumbing to his own systematic control. Whereas Elena, and here’s where the theory comes into play. I think that this film shows Elena as a figure of purity in that, as you were saying in the beginning of our talk here, the people who are evil in regards to drugs are the pushers. The ones who tell you, “you gotta do this, you gotta this. You gotta do it my way. It’s gonna open your mind,” everything. Whereas, as you were saying, if you want to experiment safely, do what you want to do. It’s your body. Elena refuses. And she refuses in every way she possibly can. She either sleeps whenever people are trying to communicate with her. She tries to attack them if she can. Or, and this is one of the most wonderful blink and you miss kinda moments– even though there’s nothing you can blink and miss in this movie, it’s all slowed down so you can experience it– They have the TV set to just documentaries all day and brochures and stuff. And at night they turn it off, and I love that she touches the screen, and uses her powers to start watching cartoons and other television programs, which confirms to her that there is a world outside of the existence that she’s in. Because she can control what media that she watches, instead of the media that’s given to her. So she’s already outsmarted them on the language of communication. Or on the level of communication and language. And that I think is what makes her so capable and able to get out of her situation. Is the fact that she’s just not having it.

DK: Yeah.

S: And she knows better.

DK: You’ve hit so many nails. That’s a very beautiful response because– just because she doesn’t say much in the movie doesn’t mean there’s not a lot of substance to her. And I praise the actress; it’s hard to do something slowly and effectively.

S: (chuckles) Yes it is.

DK: When it comes to dystopia, all they need you to do is buy it. And like you said from the get-go is “I don’t buy it. I don’t think that I need to be here. And I’m going to do everything I can to get out of here.” There’s no saving the people there; that’s another sort of implicit– Like, she doesn’t try to see her father. She doesn’t try to stop Barry from killing anyone else. She just– “I just have to get away.” You just have to get away because they’re insane. There’s no trying to reason with– This is evil on the level of impossible to reason with because they’re so certain. Because they’re insane, or addicted to Control, or on drugs.

S: (laughs)

DK: And that’s brought up in Mandy as well. There’s no talking to them. Everything they say is gibberish that maybe you can understand a little bit, and see as mythological drug-induced nonsense. And that’s scary, we don’t speak the same language. Y’know, we’re both human beings, but you come in here talking about “horns of Abraxas.” I’m really happy that you brought up that she uses the TV as a way to like remind herself there is an escape. And that when she gets out, there’s a glowing TV through the window. And that’s an image that lots of people have– matte painting by the way. For the final suburbia is a matte painting. God, I love it.

S: You can see it’s beautiful. I love that they brought that in there.

DK: And lots of people bring up, like the sinister eeriness of the fact that there’s a TV in that window. That, y’know, Arboria has TVs. And Reagan’s coming through on them. And the whole premise of dystopia is especially many of the greatest works were written as a way to say, “Hey we live in one!” And is there an escape, slash “have you really escaped if what you’ve walked into is 1980s suburbia?”

S: (laughs)

DK: But yeah, I think that Elena have a character to her, but because she was born in a cult the journey is to discover herself. Which is a mythological foundation for a character that we can empathize with. Um, also the crystal dampening her powers is such a great, like– She can’t be herself here. “The air itself is hostile to me.”

S: Yeah. It’s an environment that is literally made to be the antithesis of her comfort zone and ability to live. It’s poisonous.

DK: Yeah, a prison just for you, is Kafka. And also she makes me think of in real life. Some of the most inspiring examples of human endeavor is the fact that children born in cults will be like “fuck this. I gotta leave.” Y’know?

S: Yeah.

DK: Which is a sort of like, a good little nature versus nurture argument for, y’know, you think you can just raise someone to be a robot, if you control their environment. But if they recognize, “I’m not supposed to be hurt by someone who says they love me.” And they don’t buy it and they wanna leave. And there are historical examples of children who were born in cults, raised on the nonsense, and went “This is nonsense. I don’t even have anything to compare this to, and I know it’s nonsense!”

S: Actually, I wanted to chime in on that because you were saying something earlier about what makes this so scary with the two main figures we have, at least– three if you count Arboria in this film, between Mandy and Black Rainbow. Is that we don’t speak their language. So you have the whole, if I don’t speak your language, that makes you even scarier to me because I don’t even know what you’re trying to get at, and you’re unpredictable. But I think the key factor is, as you said “the horns of Abraxas.” That really clicked with me, because they’re up against metal-heads in Mandy, so they’re really used to language like that. And in this film, she grew up in this world. This is all she’s ever heard was this mumbo-jumbo about us “forging a new age” and all this crap. And so I think that they actually have the tools to speak the language. And the language is power. They can sniff through because they know what power sounds like. They know it when they hear it. And after a certain amount of time, you just go “But I’m tired of doing it your way.” That’s what Barry does. That’s why he takes over and usurps everything. He was tired of doing it somebody else’s way. And I think Elena– instead of having that masculine approach to it of just, y’know, storming the castle and taking it over– she’s like “I just wanna, I dunno, be a hermit somewhere. And live in the woods. And I wanna meet a squirrel and make a little friend. I dunno. I just wanna live in the cartoon, if I could.” So she just wants to go away.

DK: And there’s power in that. She’s holding her power.

S: Exactly.

DK: She doesn’t want to use her power on anyone else. And I think in Mandy, you’re introduced to them as a couple who’s so in love. She’s choosing to be with someone she loves. And that is also using her power.

S: Yes.

DK: And the great violence of the movie is tearing these two lovers away. I know, I like that too. Damn, I’m trying to remember something I was going to say earlier. Oh, when you said language– Yeah! When Mandy’s being menaced, Jeremiah says, “Look at me, what do you see?” And she says “I see the reaper fast approaching.” Which is a heavy metal thing to say.

S: Yeah it is.

DK: And he’s a hippie. So there’s a thing I really wanted to bring up, and I’m really happy I remembered it. He says, “Well I recognized you, and I think in time, you’ll recognize me.” Which is hippy-dippy, like, cosmic stuff. But the idea of recognizing something without prior knowledge of it. Which is a sort of magical concept, but also sort of hypnotic– We’re messing with your memories and time. Cosmatos said that his inspiration for this movie, Black Rainbow, was being a kid at a video store and seeing horror movie covers he wasn’t allowed to watch, and coming up with his own stories. And he said this movie was one of those movies. And he jokingly, and I think this is true though, said he came up with the poster before he came up with the plot. And the poster is evocative– woman running, triangle behind her, and a weird-looking dude with a weird-looking knife threatening her. And this aspect made me realize our experience of a movie begins the second we learn of its existence.

S: Yes.

DK: Otherwise spoilers would have no power. But seeing this poster is your first sorta of, “Oh, what is this? What’s the story? What’s everyone’s deal?” And the movie delivers by showing you these characters, and you don’t see the weird-looking dude until halfway through when they reveal that’s Barry. And he opens his dagger, and he says “The Devil’s Teardrop.” And you recognize it. Because you’ve seen it in the poster.

S: You’ve seen the poster, yeah. It’s a payoff without any context.

DK: It’s recognition without the prior knowledge which is magical. Seeing something and knowing you’re seeing The Divine. Or darkness or evil. The introduction of Barry when he’s talking down the hallway bathed in red light, and we the audience go “Evil.” That’s us recognizing him. We have no prior knowledge of this character, but the movie’s aesthetics have communicated “Evil.” And we recognize that language. Which is also mirrored in Mandy, when she sees the van. She’s walking down, and everything’s red, and the music is scary, and she looks up, and she sees a van. And Mandy goes, “Evil.” She recognizes them without knowing anything about them. Which is kinda like ESP. And that’s why I think this movie’s so perfect, when we were talking about the aesthetics of Horror and of Beauty, where your brain is speaking the same language that the movie is speaking in subliminal ways. In ways that you may or may not be conscious of, but of course you’re picking up signals. Which is like the phone call. There’s so much to talk about!

S: Agh, that fricken’ phone call. So cool.

DK: That’s another great mystery that, I’ve watched the movie four times, and I have kind of an idea of what it might be, but there’s so little information to go off of.

S: Yeah, I can think of it like in an allegorical sense or a metaphorical sense. We have the fact that Barry’s already, like how you said, he’s under the foot of Dr. Arboria. But it also shows in this moment with the phone call. So again, if you haven’t seen the film yet: he gets a strange phone call, where it’s just garbled almost like old dial-up modem kinda sounds coming in through it. Clearly whatever it is is some sort of digital existence talking to him. He understands it perfectly. He responds to it. But then after the phone call, he’s very upset and he notices– he just checks real quick– ‘Cause he tries to call Rosemary afterwards, but the dial tone doesn’t turn on. And he looks, and the phone was never even plugged in! So you have this really bizarre, like “what’s happening?! How did this happen?” And we don’t know if it’s like a drug-trip that he’s experiencing. I think it’s him– at least not on a literal level, like I said a metaphorical level– He’s yet again showing a moment where he’s not actually in control. And he’s always underneath somebody else, who is dictating to him what is and isn’t proper. As you said, it comes back again in the car. When he sees this superior, who is himself, that’s giving him the okay, like “This is good. What you’re doing is good. You can continue.” And it allows him to continue because he doesn’t have the bravery to take responsibility for his actions.

DK: And even that image is himself, so it’s like: “Finally I’m in control.”

S: Yes!

DK: But he thinks he is, and he’s smiling because he’s like, “I’m in control,” but he’s giving into these sordid desires that, like your quote– I really loved your quote by the way.

S: Thank you.

DK: That an ugly soul that is giving into so many urges and thinking that that’s the right path, but it only leads to more suffering, so they’re actually confused, but doubling down. Which is kinda like you said about male figures being told they’re not in control and them being like, “I’m gonna double down,” and staying in control. And he thinks he’s escaped the system as well, but he’s still subservient. And that true freedom, at least Elena’s the one that gets the closest to true freedom. But her journey is so abstract, but it’s like giving up. It’s allowing the Beauty to stand before you and not feel like you need to grab it. Just looking up and seeing a galaxy and going “Wow!”

S: Yeah! She’s pure in that sense. I have mentioned Kant a few times; I’m gonna bring up Kant again. The disinterestedness. That mode of thought that we need to have to experience Beauty is– Elena’s not going outside to go look at the stars, to find a constellation, to see what the outside world is like. Elena is escaping from something. And then the first thing she sees is the expanse of the universe before her. And she just experiences it and goes “Whoa!” And then imagines or possibly even sees what galaxies are. That is a wonderful visualization of what that, like attitude is, that aesthetic attitude of just, “I am watching this for what it is. And I am experiencing it on its own terms. And I’m letting this Beauty just wash over me. Because I’m allowing it to be there. Because I’m not looking for it.” If we look for it, it’s a lot harder to find. I feel that a lot of critics get caught up in looking for what they think is Beauty, but what really they’re looking for Goodness, Structure, Form, Appropriateness. Things of this nature. Things that have criteria. That are so rigid and strong that “is it sufficient?” Y’know. It actually causes you to be cynical and to nitpick and not actually see any good in anything.

DK: Right.

S: You just look at all the negatives and then say– and everything else is fine. But when we’re looking for Beauty, the best thing to do is not look. Well, not to look for. Just to experience. And I love that you brought that up.

DK: Not to define, which when we break down that word, it’s to split infinity into finity.

S: (laughs)

DK: It was Guillermo Del Toro who said he doesn’t like to call things beautiful because that by definition means something else is ugly.

S: Yes.

DK: And I was waiting for you to bring that up in the first episode. And I was like “Ah, I’ll bring it up on mine.”

S: I did not find that quote. I wish I had that quote; I would’ve done so.

DK: I think about it all the time because it’s like, yeah he shows things that are ugly or beautiful and it’s all up to us to make our definitions. But the real point is, there should be no definitions. It should just be existing, and that Barry is the deepest down-level pit of evil and Horror and wrongness because he’s done everything he can to define Beauty, to capture it. To pervert her purity. I just love that, in this movie, he calls this beautiful so many times. But they’re always in a perverse way. It’s always him saying that her mother was beautiful. He says, “You’re so beautiful when you sleep.”

S: (laughs) So weird!

DK: And also I love that his security footage of her, she’s like very small in the corner of the room. It’s obviously the only security camera they have on her, so she’s this little blob on the corner of the screen, but he’s obsessed with her.

S: Like a fly that’s always in his room, and he’s always staring at it.

DK: And Arboria. He says, “isn’t it beautiful?” about the nature videos. Again, there’s that simulation of nature. We’re separated from it and being shown this fallen version of it. But if we’re satisfied with it, and we say “that’s beautiful!” we’ve cut ourselves off from the infinity. The undefinedness of it all. And then, moments after, he gets a shot of what could be heroin or morphine, and he says, “Oh, isn’t it beautiful?” And it’s like–

S: The drugs.

DK: –there’s that perversion. You’ve actually ruined Beauty by announcing it. And Barry says, “it was so beautiful, like a black rainbow.” Which is a wonderful oxymoron of like, we can’t know what that looks like. It’s an experience. He’s describing an experience that he is calling beautiful, but he’s evil.

S: I actually think that some of this comes from the philosophy of Plotinus. Because when I was reading this, he doesn’t explicitly mention a black rainbow, but he does talk about color. And in that, like a lot of theorists, especially way back then, they were looking at form as a sign of Beauty than other things like color, and “the lesser important things of art in their eyes.” But he did say that the perspective of an ugly soul would be that color would be all shades of gray. Y’know, it would just be black and white. You wouldn’t be able to see or experience color, because colors would have no meaning because you’re not– you’re evil. You’re ugly. You don’t have Beauty. You don’t experience Beauty. So if there was Beauty in color, it’s stripped away. Which was also a way for him to try to take away the fact that color could even be a factor in Beauty because it’s so easily destroyed in his eyes.

DK: Yeah, just trying to not to do homework. (laughs)

S: Exactly. Um, for the sake of time, we could go on for hours and hours and hours, but I do like to keep it a little tight. So I do have one closing question for you, which is a difficult question, and I want you to try to unpack it. So we’ve gone in. Let’s look at that quote that I have, and I loved how you gave your most recent description of Barry, and not only his search for Beauty. But his void basically of self and of existence to a degree. Would you say, yes or no, with all of this in mind about Barry, is he still a beautiful character?

DK: Ooh, that’s uh, I wasn’t ready to answer that.

S: (laughs)

DK: Um, if I were to be hippy-dippy, I would say we’re all children of God. We all have a chance to be beautiful. Um. The image of the movie that I find most frightening, which maybe here’s your answer of the most beautiful, is the moment after he comes out of the pit. He’s drenched in black tar. He kills Anna. He stands there, and he looks like a Rodin sculpture, and I was looking at it and I was like “that’s fucking evil.” But he’s so expressively sad.

S: Yeah, he is.

DK: And I think Barry’s a beautiful. I think yes he’s a beautiful character because, in the way that Aristotle would say Tragedy is a beautiful genre and mode of human emotion. And I think the journey Barry takes us on is a beautiful one. So to answer your question: yes. But I also think that evil needs to be eradicated.

S: Yeah, no, I’m not trying to glorify evil. (laughs)

DK: And he makes himself an avatar of evil. I think he’s a monumentally tragic figure, which are the best monsters. Not because I feel sorry for him, but because I understand why he’s doing it. And he is doing it because he’s hurt. I’ll say yeah, the movie shows all of these nooks and crannies of him, and that his cornerstone is: he’s fucked up. And it’s really sad to be fucked up. So to answer your question: yes.

S: Excellent. I really like that answer. Thank you for taking the moment to just really unpack that. I don’t feel there was a necessarily right or wrong answer. I wanted to challenge that, and I agree with you. And I also think that this episode and this discussion. I want to thank you for bringing this film because I do feel that this helps me take that next step into what I’m trying to teach with this podcast. That through the lens of Beauty, you can have different considerations about motivations, characters, situations. Things that on the surface– that would otherwise trigger you or cause you discomfort or cause you pain– could be this knee-jerk response to say, “but it is just wrong, it is just worthless.” Y’know? And a character like Barry is easy to write off as just base and not worth any analysis. But the analysis becomes really clear if you ask yourself this question: can I still see Beauty in this? If you can answer yes, you have to ask yourself, “Why?” And that is where the real work comes into play. And that is where the connection between Beauty and other discourses comes about. That’s where the intersectionality comes into play. That’s where I’m coming from, is to kinda show there’s still a space for these political discussions, there’s still a space for the social discussions and for emotional discussions. In seeing the hierarchy of Beauty, in seeing the discussions on Beauty, and looking at the world through the lends of Beauty doesn’t take this away. It depends on your perspective and what you do with it. You could be an Arboria and a Barry and try to strive for your ideal of Beauty and just lay waste the whole way through. This is where we get evil people in the world. They have an ideal that they’re trying to achieve. They want beautiful people around them with beautiful cars and whatever aesthetic that they enjoy. However, you could also see things from the viewpoint of, “the fact that there’s still a semblance of Beauty in something I find hideous and disturbing means that there’s a complexity to this that I haven’t actually given enough thought.” And Barry’s an easy, easy character to write off. And I think that this discussion has been a great example of how complex things can be if you take that step to unpack it. Just by saying there’s something tragic here, there’s something melancholic, there’s something beautiful to his existence. And I loved that you brought up that shot because it’s exactly the shot that I think tipped it for me as well. Is him looking, just aware of the fact that he was dead basically, he was destroyed, he was unmade. And now he was something new. And he wasn’t happy with it, because he was pretty happy with who he was before. And you even see parts of him drifting away from him. This black goo, kinda coming off of him. And he’s just drained. He’s a husk. And I found it so tragic to see that it was put upon him. And then we see who he is later in life, and he’s still just pathetic and evil and horrible. Because he’s pathetic, because he’s been so drained by somebody else. He’s been put upon.

DK: That word, pathetic. I said the universe is pathos. Emotion. Feeling. We get the word “path” from it. We also get the word “pathological.” It’s the path we walk. We do it and it is done to us. And I see Barry as someone who is given a very bad path.

S: Very much so.

DK: Movies are also the thing that keep us separated from it. If we were around him in person, we’d be like “That’s not beautiful! I gotta get outta here!”

S: Oh, no, no. That’s a threat. That’s a different thing.

DK: And I think that’s the power of the genre, is to show us something we shouldn’t see in real life. But we’re allowed to see it when we put it in a case. And this movie is a case. And I think it’s perfect for your podcast because I think Beauty cannot be seen, Beauty can be experienced, kinda like your terrible Beauty quote. It’s not– it’s a confluence of sensation and experiences. And that it’s not an image, it’s an image with a lot of context to it. And ultimately I believe it’s impossible to describe. It’s just felt. And that it’s beautiful to share those feelings with other people and to have a community that can share it in art. But ultimately it’s kept from us. Just like Elena is kept from Barry. And just like meaning in the universe is kept from Barry. He can’t stand it. And that’s one of the things that drives him, is that he refuses to not grab Beauty.

S: I think that was a great way to close off. I wanna thank you so much for this very thought-felt, intricate conversation. But we’re gonna wrap up then. So! This podcast is part of the Anatomy of a Scream pod squad. Be sure to follow the Anatomy of a Scream podcast page on your preferred podcast platform to check out more introspective, semi-academic and fun podcasts including The American Beyond, hosted by Justin Yendel and Kristin Van Kay. Nightmares and Dreamscapes, hosted by Terry Maynard and Joe Lipsett. And much more. You can find more information at anatamoyofascream.wordpress.com. If you’re interested in more of my musings on Beauty in Horror, or just Horror in general, you can follow me on Twitter @_shockaholic. And you can find my written work at Ghoulish Media and Morbidly Beautiful. Be sure to keep track of the podcast on Twitter and Facebook @beautyhorrorpod. I wanna thank David again for this lively and wonderful discussion. So where can the people find you, and is there anything going on that yo might want to plug or push or anything like that?

DK: I do have something going on.

S: Ooh, do tell.

DK: You can find me on Twitter; I’m more active on Instagram. I have a comedy-horror video coming out. Most likely by the time this podcast airs; it’s in post right now. I filmed it in quarantine with the very amazing production company Too Lemon Productions. You can follow them on Twitter or Instagram. I play a nightmarish doctor who is going to drag you into a cult.

S: (laughs) What a fitting character!

DK: Oh yeah, it’s going to be free. I’ll be blasting it everywhere, so if you follow me or Too Lemon, you’ll definitely see it. We’re very proud of it; it’s coming along really great.

S: Alright, thanks again, David. I had a blast talking about this. And really, check it out, this movie was quite a treat for me as well. And thank you, dear listener, for joining us in talking about the Beauty that lurks within the Horror. Goodbye.

AUDIO SAMPLE FROM “I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE”: There is no Beauty here. Only death and decay. (echoes)

ANNOUNCER: The Anatomy of a Scream Pod Squad.