In 2020, Chandler Bullock a.k.a. Shockaholic was kind enough to host me on their podcast Beauty Of Horror. Our topic was Panos Cosmatos’ masterful film debut. You can listen here and follow along with this transcript of our conversation (I edited out some of my copious stammering):

ANNOUNCER: This is the Anatomy of a Scream Pod Squad network.

AUDIO SAMPLE FROM I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (1943): There is no beauty here. Only death and decay (echoes).

SHOCKAHOLIC: Welcome to the Beauty of Horror, a podcast dedicated to exploring the unsettling beauty found within our favorite genre. Each episode I’ll sit down with a different guest to discuss a horror film they find particularly beautiful and why. I’m your host Chandler Bullock and today’s guest is an LA-based writer, comedian, and horror fan who likes to meld the sinister with the absurd. Beautiful welcomes to David Kane!

DAVID KANE: Hello! Happy to be here, thank you for having me.

S: Oh, it’s delightful to have you. I’ve enjoyed our brief correspondences up until now, and it’s gonna be a delight and a pleasure to talk to you today about the film we have in mind. How’re you doing?

DK: I’m doing quite well. I’m all jacked up on this movie, I’ve been thinking about it all month, I’ve been writing so many notes. It’s so perfect for your project. I’m a huge fan of it–of your project.

S: Well, thank you.

DK: Yeah, and I’ve also been watching lots of Horror this month, thinking about everything you’ve been saying on the show. Y’know, it’s actually affecting my lens when it comes to the genre. So thank you!

S: Well, that’s the goal. That’s a big ego boost for me, thank you for that. Really happy to hear. That’s the goal: to see if we can get people to just try to reevaluate the way they watch films, especially Horror films. Before we get into the film that we’re gonna discuss today– which I’m really looking forward to hearing what all you’ve written down about it– I do like to kick off each episode with a quote that pertains to our topic. Usually from philosophy, and today is no different. As you listeners are very aware, I tend to take my time with this, and today’s no different. In fact, I think this time it’s actually the longest quote I’ve had so far. So, we’re going way back, back to antiquity, back to some of the earliest philosophy. But here we go, let’s get into this quote, and hopefully we can try to make the link with this film. I think it links pretty well, but we’ll get into who said it and all that a little bit later. But first, here it is:

“Let us suppose an ugly soul: dissolute; unrighteous; teeming with all the lusts; torn by internal discord; beset by the fears of its cowardice and the envies of its pettiness; thinking only of the perishable and the base; perverse in all its impulses; the friend of unclean pleasures; living the life of abandonment to bodily sensation and delighting in its deformity. What must we think but that all this shame is something that has gathered about the Soul, some foreign bane outraging it, soiling it, so that it has no longer a clean activity or a clean sensation, but commands only a life smoldering dully under the crust of evil; that, sunk in manifold of death, it no longer sees what a Soul should see, may no longer rest in its own being, dragged ever towards the outer, the lower, the dark?”

Again, I will reveal who said this in just a moment and talk a little bit about what that all means. I just wanted to bring that in there, but I did feel that it has a little bit to do with today’s topic. But again before we get to the topic, let’s talk a little bit in general about you, David. So what is your relationship with this wonderful genre that we tend to explore here on this podcast? How did you first start getting into Horror?

DK: So when I was a kid I saw Jaws, and it was seared into my mind because it was the first time that I saw a kid die in a movie.

S: Yup.

DK: It might have been my first confrontation with mortality. And the kid dies hard.

S: (chuckles)

DK: And I loved the movie because it was man confronting this monstrous force. Also, I don’t remember how young I was, but I was young enough to mishear, misunderstand the opening scene where the first victim is killed. As she’s thrashing in the water, I thought she was saying “Jaws, no! Jaws, no!” And as a kid, I was like “Jaws is the name of this shark, a local neighborhood shark who has lost his mind and started attacking people. And that’s the horror, is that no one knows why. And that fits into the movie ’cause no one knows why this shark has started killing people, but as a kid I misheard that, but it fit into my viewing. And I’ve always, from then on, have sought out movies that I felt like I shouldn’t watch. When you’re a kid, R is this ominous shadow that looms over you. Every genre has a pledge, and the pledge of Horror is to scare you.

S: Right.

DK: And it’s so titillating to be like, “this is a feeling I’m not supposed to feel. My body doesn’t want to feel this. And I’m going to make my body feel it.” Like a roller coaster. But Horror has you confront these ideas like mortality or the monstrous. And you face them and survive them. And I think that as a fan community, we like watching characters survive something because we want to, too.

S: Oh for sure. Yes, I love how you put that. That confrontation, that element of Horror is something that has driven me throughout my entire studies as well. It’s something that I came across really early on in my studies, for film studies. They talked about the paradox of Horror. So that paradox being that why do we seek out something that’s unpleasurable to us? Something that actually causes us to be confronted with these darker shades of ourselves. Or of the horrible parts of reality, such as mortality and the evils that people can bestow upon each other. It’s been an interesting path and journey to get there, so it’s really lovely to hear your own perspective as a fan. Y’know, from that young age it just clicked it’s right there from the very beginning. You see something that’s terrible and here you still are, talking about Horror now on a podcast.

DK: Yeah, and in Jaws they win. And it feels good at the end. As a kid, I feel like had it ended on a more cynical note I would’ve been more shaken. And as I matured as a person, I definitely was seeking out like, “okay what’s the dark stuff?” Y’know, what’s the stuff that is trying to say something more than, “yay we beat the evil”? Y’know, the nature of evil being so much more complex than just a battle between the light and the dark. Especially when it comes to “who is the monster?” What dimensions does the monster have?

S: Oh, and Jaws is a great, great movie for that, considering you’re looking at nature just doing its thing, and we’re doing everything in our power to suppress it. And at the same time, we’re doing everything in our power to keep each other safe, except we’re not. That was the whole point of that film was to show how corporate systems really are more evil than any man-eating shark could ever be. It’s just doing what it does.

DK: That and Alien, when I was little bit older I snuck Alien. Like, I watched it alone, and it completely terrified me because Jaws is set in our world, and Alien transports you, but it tells a very similar story. Like first it’s versus some kind of nature, and then the second twist through being the Company doesn’t care about us. And that double-pincer of like, “you’re alone in the universe, and everything out there wants to kill you.” As a creator, as a writer, I love Comedy. I think it’s a cousin genre with Horror because they’re both structured on surprise. You’re not expecting a punchline in the same way you’re not expecting the scare. [or the creator is trying to subvert the expectation of the scare] And especially with tone, they’re both genres that love crafting the tone that the viewer is supposed to feel.

S: Right there with you, I actually come from a comedy background myself. I have other ten years performing improv in front of audiences and stuff. It was funny how Horror has always been a part of my life, and Comedy was a great kinda escapist genre for me as a kid. But the more I watched it, the more I emulated it. The more I wanted to be Jim Carrey and be Robin Williams and all these stars on SNL at the time I was watching it at least. In my studies as well, I’ve come across that there is that line between the two of them. They’re kinda two sides of the same coin to a degree. And it’s that surprise you’re talking about. Incongruity is a huge part of both of them. The major difference of course being that in Comedy there’s always a sense of safety there at the end of the punchline. And in Horror, you’re just immediately confronted with something. Or, if you’re not, then it’s played for a laugh. And that laugh is there to disarm you for when shit gets real basically.

DK: Yeah, I think they both approach Dionysian levels of consciousness. Send the audience in to fits of laughter or fits of screaming. I took a class on Grotesque Literature.

S: Aw nice.

DK: We studied Kafka. We watched Eraserhead. One aspect of it that shot straight into my brain was: the audience, when experiencing the Grotesque, isn’t sure if they should laugh or scream. It’s ridiculous in a way that attacks a very deep part of them and they are uncertain of how to respond, which is a disorienting experience. Horror and Comedy disorient people in various ways.

S: Yes, yes, I love that you brought up the Grotesque. That’s actually one of the gateways to me even starting this podcast. So I took a course on the Beautiful In Film, and that was the one that I thought, “Oh I just need some credits,” And I’m doing Philosophy With Film. Sure, I’ll do the Beautiful even though I was pretty sure that we were gonna talk about films that I would probably never watch otherwise. And it was gonna be a lot of foreign arthouse films, y’know? Very slow, nice, gentle films. And there were quite a few of those. But before that was of course I really eager to take was the Grotesque In The Arts. And in that one, we analyzed very similar concepts in the Grotesque. We didn’t watch a lot of movies in that one unfortunately, but we did talk about some examples. But I liked with my professor there, she mentioned that if we were to look at the Grotesque as a sort of liminal space between Beauty and the Sublime. Beauty is this kind of gasp, this Oh! That you’re awestruck. The Grotesque is a shiver. And I loved that description of it, that it’s this kinda egh. And that you don’t really know what to do with it because on one hand you’re drawn to it. Otherwise we wouldn’t be drawn to anything Tim Burton’s ever made basically. He does a lot of kid stuff and yet we’re still drawn into the big googly eyes and the misshapen characters that he has. But we’re also repelled by them too, they’re very off-putting, and we wouldn’t want to see them in our daily lives because it doesn’t fit within the mold of reality basically. This form of hybridization and you’re right: Horror plays with that a lot too.

DK: Yeah, seeing something we shouldn’t. That was the voice in my head of like, “You are not allowed to watch this. Cross that forbidden line. Man was not meant to know these truths.” Love that!

S: That’s some of the best form of Horror out there: the unknowable. Y’know, I think we’re nice and warmed up. So tell everybody, David, what film are we talking about with all these high concepts that we’re bringing to the table?

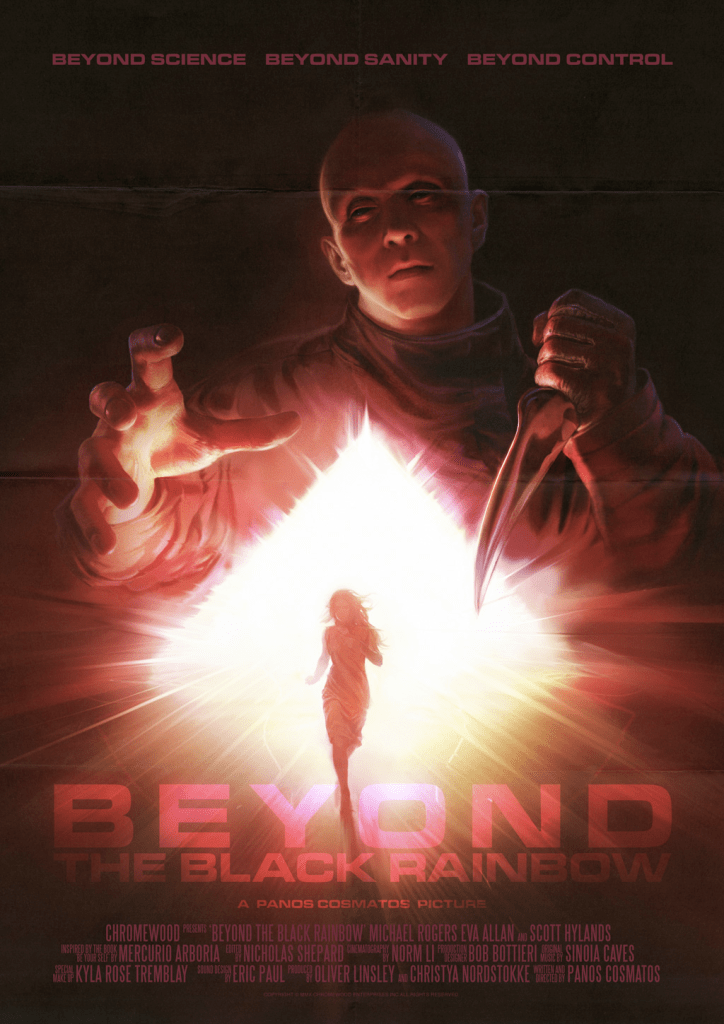

DK: We are talking about the debut feature from writer-director Panos Cosmatos: Beyond The Black Rainbow.

S: Ooh, Beyond The Black Rainbow indeed.

DK: I love a movie whose title is fun to say.

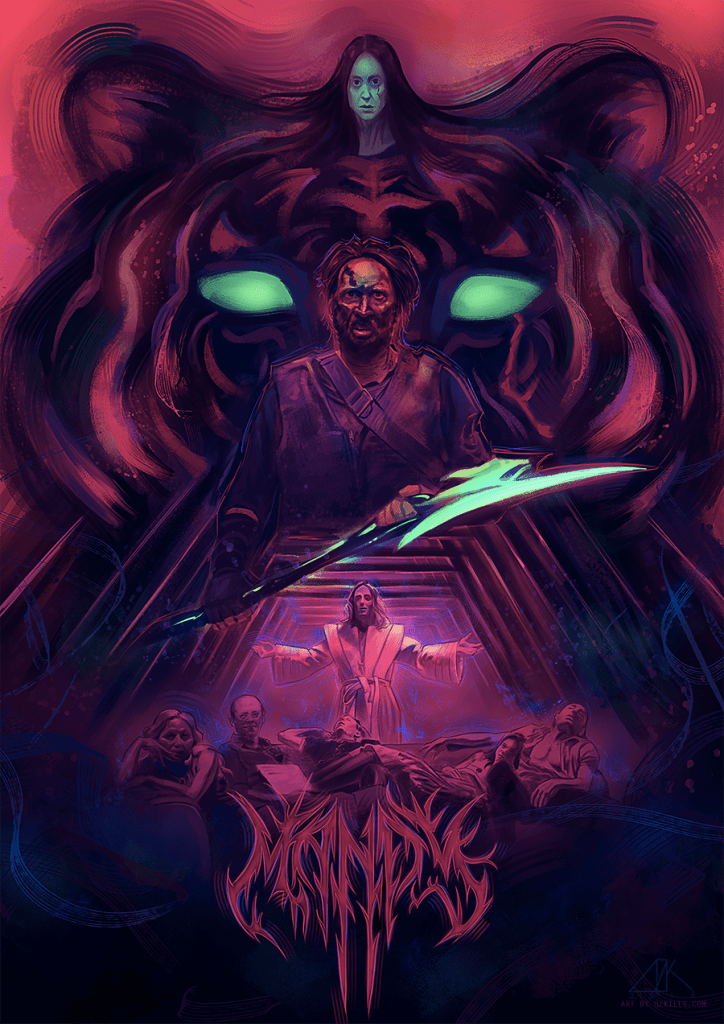

S: Right? And Cosmatos, apart from maybe Mandy, visually it’s always fun to look at, but I’m not surprised that he would make such a wonderfully kinda vague and artistic title for this as well.

DK: It draws you in, yeah.

S: It really does.

DK: The title is an invitation. And that’s the thing is you accept the invitation at your peril, which is the entire genre.

S: Pretty much, yeah. And I love that this was a nice mix of genres too. So yeah, this was a first time viewing for me. I watched it a couple days ago, and then I watched it again today to just like absorb it and really focus more on the aesthetic parts now that the story was a little bit more ingrained in my head. And I have to say, yeah, this was an interesting film to watch and a lovely beautiful rich example of what we like to talk about around here too. That quote that I brought in, I can’t wait to unpack these things. But for anybody who hasn’t seen this particular film, I know that Mandy‘s the more popular of the two.

DK: That’s why I picked this one.

S: Yeah, I’m really happy you did.

DK: I want more people to know about it. It’s also, a warning: a tough watch. It’s cliche to call a movie bold, but I think this movie is bold because it is boring sometimes. Or it can be! In multiple interviews talking about it, [Panos Cosmatos] said “I know that’s a lot to ask of an audience.” And the movie asks a lot of its viewer to stay in. One of the reasons why I loved it on my first viewing was I was like, “I’m here. I know not everyone who started it is here. But I’m here.” I picked it because also I could talk about this movie for hours, and I will.

S: (chuckles) Well we have time, that’s good. Yeah, my partner also had that feeling of it being a little slow. She was just saying a moment ago while watching it with me for my second viewing. She’s like, “This is not a movie that I think I would ever pick up myself. Normally I wouldn’t sit through this.” But she knew it was gonna be for the podcast. It did draw her in enough that it kept her going, but there was one moment that I remember there somebody was just leaving a space. And I had to walk around and put my setup together, and I think that took me about five-ten-ish minutes. I went into the office and came and gathered my stuff, and then I came back out, and I’m like “What? Wow, are they still in the doorway??”

DK: I think I know exactly what moment you’re talking about, and that was perfect. My wife was also bored. I was worried. I showed it to my wife, and I was like, “did I pick the wrong movie for the podcast?”

S: No!

DK: I applaud– ’cause, I don’t know. Watching it amid so many movies that are desperate to appease its audience, to presume what its audience’s sensibilities are. And this movie came along. I just think that he asks a lot of his audience, and it’s great when a filmmaker trusts its viewer so much.

S: Yeah. I do appreciate that. And most of my favorite filmmakers do the same thing. So again, for those of you who haven’t seen it, I have tried to make a synopsis for this film. The problem with making a synopsis for it is that I could pretty much tell you the plot of the whole film in maybe three sentences. It’s a very simply story. Which is where the aesthetics actually thrive, it has a very sensual or sensuous sort of existence. And that part of it is vital to the whole experience of the film. So that you understand the significance of the story a lot better. So if this sounds very vague, it’s intentional. The movie’s not as quite as vague was what I’m about to say to you. But still, for those who have not seen it, here’s a brief synopsis. And decide for yourselves if you just wanna plough through and listen to our spoilers or go watch it first. I can highly advise you do that, thought, ’cause this movie is just worth watching blind for sure. Here we go:

1983. An enigmatic and sensuous scientist by the name of Dr. Barry Nyle oversees and experiments on the young helpless Elena. Elena remains captive in a sterile cell underneath the Earth. Why is she here? What is Dr. Nyle’s goal? All becomes clear(er) as he follow Dr. Nyle’s descent into madness and attempts to transcend to a higher purpose. His and Elena’s metaphysical journey toward true freedom ultimately begs the question: who would you be if you came face to face with The Divine?

DK: I love that synopsis.

S: Thank you! That’s the best way I can put it. (chuckles)

DK: One of the things I love about this movie is that it is hard to talk about. So many plot points if you could call them that are assumptions based on the viewer. And you have to zone in on what you think you saw, what information you think you got from an image. And think about how much of that knowledge was from the movie and how much of that knowledge was you filling in space.

S: Mhmm.

DK: I’ve read lots of reviews and lots of synopses where people got details different. And I’ve been both, “that’s wrong, it happened this way,” and “wait a second, I thought it happened this way, and I think you might be right.” And there’s also moments where it’s like, “I think the movie might be so vague so no one knows what happened there.” That’s a feature, not a bug. It’s absolutely a movie where everyone who’s watched it has had a shared hallucination which we’re trying to piece together what happened sense-wise and then what knowledge we shall take from that data.

S: There’s a lot of space for projection in this film. You project your own knowledge or desires or personality traits onto particular characters or moments. Of course, like any really wonderfully wild kinda synthwavey film like this, there’s also lots of imagery in here that could be very vague. Could be very clear, depending on the things that you know, and the different esoteric knowledge that you have, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that is what that is. It’s just there to kinda strike some sort of chord in you to fill in those blanks. So that you get the details that are clear, and then from there you can piece together intent and motivation as you go along.

DK: I think what’s so great is it’s not just confusing all around. There are unambiguous things that are obvious, and a lot of the plot synopses have this spinal column of information that the movie is very clear about. But it’s all orbited by these ambiguous satellites of information that are hinted at. I’ve seen it like four or five times now, and there’s stuff that I didn’t realize until my fourth viewing. And that colored my entire experience of it, and I was like, “God! I’ve been wrong about this the whole time.” Which is like, if you haven’t watched it, and you’re listening, and you’re like “what the fuck is this movie?” that’s it! It’s such a great mystery of a film. It’s an artifact from the past.

S: Yes, it’s definitely an artifact of the past. And it’s so much of a mystery of a film that even the synopsis that is official doesn’t really tell the story of the film. It says just straight up, “Elena wakes up and discovers that she’s being held captive and wonders what’s going on,” and that’s not how this movie starts at all! That’s not even true!

DK: Exactly! The shared knowledge. The clouds of information passing through each other, and realizing like–There’s an exo-psychology experiment that goes: a group of people walk down a hallway into a room and are told, “picture that hallway you just walked down and list the items you’ve seen, list information about that hallway.” And everyone does it, to show that we all walked down a different hallway. Because we all have a different–We all experience reality our way. But we exist in consensus reality. And this movie has this, like, jamming signal that scatters everyone’s experience of reality.

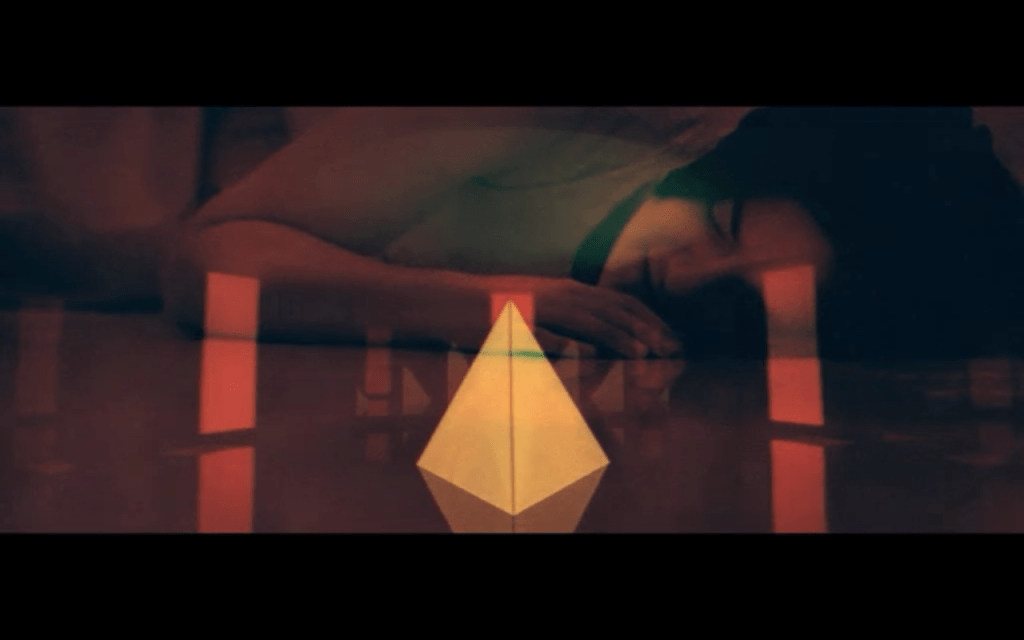

S: Which is an actual plot point of the film as well. To add some clarity for people who are listening, in case there are some people who are like, “I just wanna listen to this and didn’t watch it.” There is an actual jamming thing in here. So Elena has some sort of either mental powers or something. All that we know is that she has some sort of strange abilities that has caused her to be kept captive in this scientific chamber. So it’s a throwback to things like Firestarter. You can see references in Stranger Things and in other movies of this nature. Phenomena comes in there.

DK: Tons of early Cronenberg.

S: Yes. Lots of Cronenbergian stuff in here. And to keep her at bay, there’s this pyramid that seems to create some sort of a signal that keeps her powers from basically melting everybody when she gets emotional. And that jamming device, I liked how you pointed out that it’s actually something that affects the viewer as well. Just because it’s such a vague film that you don’t really know what the purpose of most of the stuff is. All you’re gonna be able to tell–I think that this podcast might be the perfect way to watch it because I was just so focused on the aesthetics that I followed along, I felt pretty okay, just ’cause I was like “okay, oh well yeah y’know, based on the sound and the images here. I just kinda vibed with the mood the whole way through, y’know?

DK: So if I can go on a bit of a rant.

S: Okay.

DK: The way that information is given to the viewer in this movie, there’s a pattern. If follows from dialogue to the cinematography of scenes to the way that plot is constructed where it’s nonlinear. You are given pieces of information that you don’t understand, and then later, like, for example a character will start a sentence mumbling, and you won’t understand the first word. So you write off that first word, but then you do understand the next two words. So you retroactively, “Oh he must’ve said that first word in order for this sentence to have continuity.

S: Mhmm.

DK: And scenes open, many of the scenes open with textures, close-ups on objects within a room. And the viewer is instantly unsure of what they’re seeing. They see color and shapes, and sometimes–like there’s a bowl of meat. There’s a close-up of that, and you’re like, “okay it’s meat.”

S: I remember that, yeah.

DK: And you don’t see it’s a bowl, but it zooms out, and you see that it’s a bowl on a counter.

S: Yeah, it’s porkchops. (chuckles)

DK: And your brain is catching up with the pace. The movie slows down the pace of your consciousness to its level and controls what information it gives you on the level of dialogue and on the level of shots in a scene. And then in the plot you see a character, and you come up with an impression of them. And then later learn past–Like Nyle, you see Barry Nyle. And what I love is one of the most unambiguous moments in the opening. He’s walking down a hallway bathed in scarlet light and a scary synth tone is played, and the viewer is like “Evil! That man is evil.” And you’re right, the movie was not mysterious about that. This is an evil man. But then you learn more details about him as the movie goes forward, so that your first impression changes shape based on the new information. A friend of mine who watched it said it was like being in Plato’s Cave. Where he thought he knew what reality–that he was shown one shape, but then as the movie expanded, he realized he was in a labyrinth of information that was constantly changing his experience of the movie at every moment. It’s psychotronic cinema at its finest.

S: Ooh, see, now that could be on a poster: “Psychotronic cinema at its finest.” I like that a lot.

DK: I wanna write a book of essays about the movies of Panos Cosmatos. He needs to make more. And I’m gonna title it “A Poisoned Nostalgia,” which was a quote from an interview he did where he described Black Rainbow. He was trying to go for a poisoned nostalgia.

S: Okay. And I think he hit the nail on the head, ’cause what I loved about the–we can talk a little bit about the nostalgia of it. So, beyond just the aesthetics of it. I will touch on that briefly, but I do have a rather specific thing that caught me. The aesthetics of course is to emulate the graininess of old ’80s cameras and TVs and monitors. Hell, there was even one moment that my partner said, like, “man, the quality of these security cameras,” and she’s like, “wait, it’s 1983 of course.” (laughs) Exactly.

DK: Yeah, they used lenses from the ’70s to film the movie.

S: Perfect. ‘Cause you should always get older tech for a time period that you’re trying to do. Since most likely places are gonna use cheaper, older tech in reality. But the point that I wanted to get to is that they give a lot of information with Elena of how they try to gaslit her about what reality is. And I feel that the film through a lot of the dialogue, if it’s all you focus on for most of it, you’re gonna get caught up and swept away thinking this is some sort of alternate reality, post-apocalyptic view on 1983. And then when you’re in Dr. Nyle’s house later in the film, they have footage of Reagan talking about the war, talking about commerce. And you think, “see there’s even more proof of this.” And then when Elena gets outside: it’s just a normal day, normal houses, people watching TV. Like, ahh, I love it! I love that so much about how this movie makes you believe constantly, “This is not based in your reality, it’s too bizarre.” And then you’re like, no, this is your world. You live in the apocalypse basically.

DK: Yeah, uh, I couldn’t put it better, but I’m gonna try.

S: (laughs)

DK: One of the other reasons I picked this movie is because it did trick me. I watched it like six years ago. I was making a habit of going to video stores and buying really cheap DVDs, and I had just watched From Beyond. The really great Stuart Gordon movie.

S: Nice.

DK: And I loved that, and it was definitely the “beyond,” just these schlocky, fun to say titles, that I saw Black Rainbow. And I thought the date on it was when the DVD was made. And I love going in blind. But I looked at the cover, and was like “okay, this was made in 1983.” And I put it in my DVD player and I watched–the opening of the movie is a black screen with “one-nine-eight-three.” And my brain went, “Okay this is where we are. This is when this was made.” And I watched the entire movie. And it was the next day when I wanted to learn more about it. I looked it up and saw that it was made ten years ago. I’d actually entered a false reality, I’d created a false reality with the help of this movie in which this was a lost Christian Bale movie. ‘Cause Michael Rogers looks a lot–

S: Thank you! (laughs) That’s the first thing I said.

DK: In my first viewing, I was like “is this movie meant to trick people into thinking Christian Bale did this movie?” And it actually blew my mind. It’s a cliche to say it, but I was completely pulled into this movie’s version of reality. And it does craft its own false reality of “this was made back then” and sells it. The aesthetics of the past are its disguise.

S: Mm! That’s a good one. Yeah, I see where you’re going with that. That is a great disguise for it as well. And hell, look at Barry. He literally disguises himself as the past self he was in 1966 before he did the experiment. So he wears this terrible wig to get his terrible ’60s hair back. And I loved when they revealed all the prosthetics, and I have to wonder if the actor really was just wearing prosthetic eyebrows and stuff throughout the whole film.

DK: He’s a weird-looking dude.

S: Yeah! He always looks off.

DK: That’s the thing, like, in the first scene, there’s a closeup of him. In the first scene, there’s a closeup, and his makeup looks bad. And his wig looks fake. And I think that’s a deliberate choice to lull the viewer in this sense that like–especially when you watch movies from the past, you’re looking back on it. You’re safe from it.

S: Yeah.

DK: There’s a quote from a film historian I can’t remember that’s “The limits of the past generation become the aesthetics of the present.”

S: Okay, yeah.

DK: Which is a bit about nostalgia, but also this movie weaponizes the aesthetics of the past. You see his bad makeup and you’re like “okay, I can see the seams of this movie,” but then you learn that’s actually a feature within it. And the movie gets weirder and weirder as it goes further. It stops looking like an ’80s movie and starts doing things–like the 1966 flashback is unlike anything that was made back then. So when I was watching, still thinking it was made in the ’80s, I was like “this is ahead of its time!”

S: Makes Cronenberg look just like a simpleton, right?

DK: Right. I know. Yeah, that’s the thing. I was like “this is truly a lost gem.” It’s designed like a lost gem. Somebody dusted a gem, tossed it in a sandbox, and I found it and went “Ohh! A lost gem!”

S: In a way, it still is if you consider all the films that came out in 2010. It was on my radar when it came out. I just never actually sought it out and watched it. You know how it goes: you hear about a movie that you’re really interested in. And then you get caught up in other things and before you know it, you forgot you were ever interested. And then you hear about it ten years later, and you’re like “oh yeah, that movie. I’m gonna watch this movie now.” And that makes it a lost gem of its time. But yeah, to dupe you in the ’80s. What I love the most about it is I think the way it works and why it could dupe people, is the fact that it is a lower budget film that has a high concept and high quality to it. That there are images in this film that you would think looking at it like, “This had to be some crazy graphics team doing this.” But if you look closely, “is that just a mold of somebody’s head with a light inside of it? And then they put, I dunno, some dry ice around it?”

DK: Yes.

S: That looks awesome! And then you just reverse the image to make it suck into its face and things like this. Those are very ’80s techniques to trick the eye with practical effects.

DK: Yeah, there’s that “you’re not certain of what you’re looking at.” And that’s the thing, the movie is tricking you because it contains characters that’re tricking you. It’s got this cult, this mad scientist, these monsters. It’s about trying to control reality. One of the pledges of Horror is, “this movie’s gonna reach out of your TV and assault your senses.” And this movie does that, but it does it gently.

S: It takes its time.

DK: Yeah, it’s hypnotic. [Cosmatos] said he wanted to make the movie version of trance music.

S: Okay.

DK: He said, “if Black Rainbow is an experimental ’70s synth album, then Mandy is Black Sabbath.”

S: Yes it is. Oh absolutely. In fact, they even give a little taste of Mandy when you get into the reality at the end of the film. The two stoners there around the campfire.

DK: Yeah, I had a friend who was confused as to why the heshers are in it. And I was like, “he likes heavy metal music.”

S: He likes metal! I guess if you see both movies it becomes a little clearer. If this is the only one you’re watching– Also, it’s very indicative of the ’80s. I mean, ’80s was Metal’s heyday. So it stands to reason, if you’re gonna do wandering out randomly in the woods, you’re probably gonna find some Metal kids with a bonfire, just chillin’ out. That was pretty common, especially in suburbia as we find out where they are. You’re just in the backyard of somebody’s backyard. At that moment, anyway.

DK: I also love their inclusion– I love making parallels in movies. Maybe too much, maybe it’s a stretch, but it is dystopian where they think they achieved enlightenment and are gonna save humanity, and they failed spectacularly. And the way that Arboria ends up, it’s just so pitiful and disgusting, and that they’re not better than losers doing drugs in the woods.

S: Ah!

DK: And the last two characters you meet are just that. And Barry is supposed to be, y’know, this dark lord of Hell, but he’s just a lunatic swinging a dagger at strangers.

S: Yes, which is made abundantly clear at the first probably most deflating ending I’ve ever seen in a film. And then I appreciated it the more time went on because it shows just how pathetic Barry really is, and how, “you’re not a god! You’re not some harbinger of Doom or anything. You’re just a dude whose pupils got dilated and now you’re still tweakin’– You’re still having an acid trip for the last twenty years basically. (laughs)

DK: I love that Cosmatos movies are definitely about drugs and about drug-experiences. But the villains are always the people who want you to do drugs. The lesson is always don’t trust anyone who’s trying to make you do acid.

S: You should seek that out yourself.

DK: Right, experiment responsibly and of your own accord. What the viewer goes in with, the movie resonates with. So I really love reading up about psychedelic philosophy and the thinkers of the ’60s. Not nostalgic for it, I’m happy I didn’t live then, ’cause it was very scary. Both Barry and Dr. Arboria reminded me of Dr. Timothy Leary, the scientist who was very famous for many reasons, but he was like, the name was studying acid in the ’60s.

S: Right.

DK: And he was jailed when it became illegal. And he became the like [voice saying], “This could free humanity.” That’s the Arboria part, “This could free humanity.” But while in jail, [Leary] started talking about, like “We’re gonna contact aliens.” And, like, imagine looking up to him, and then hearing that, that’s like Barry. Where you’re this trustworthy scientist at first, but there’s something about– Especially ’cause you’re studying drugs that were invented fifteen years ago. So you’re the only one who knows anything about them. And I truly believe that [Leary] had good intentions and he wanted to help humanity, but he also had like five wives and cheated on all of them. And his third wife’s name was Rosemary, which I think is an easter egg.

S: Ah, that could be a reference, yeah.

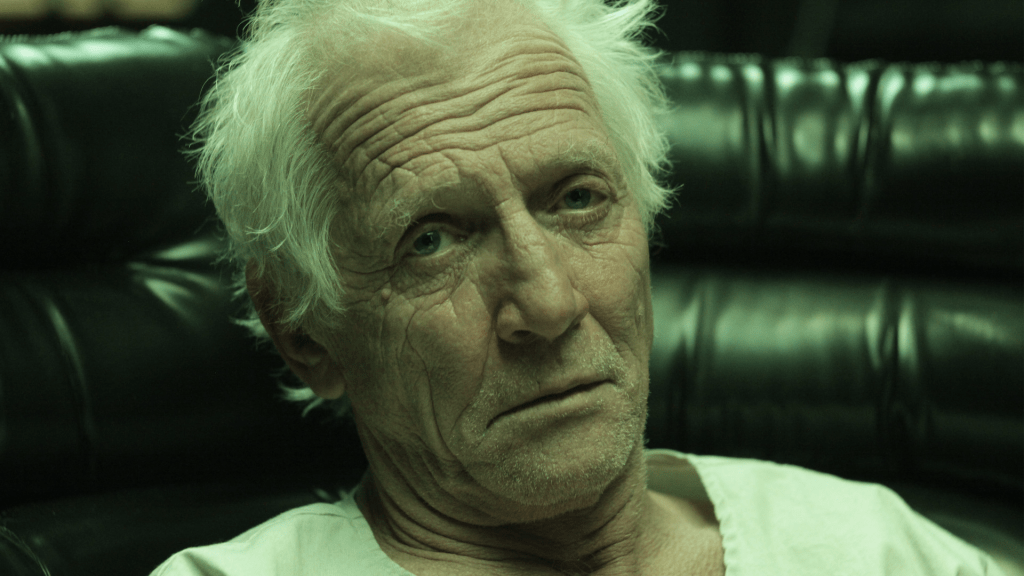

DK: Right, that’s the thing. Again: going in knowing certain things and going, like, “is that a coincidence? Is that planned? Is that a small thing?” But Arboria is scarier to me than Barry– I mean, Barry is terrifying– But Dr. Arboria is this, like, you only see him in three scenes, but you know everything about him. Where it’s just: he thought he was gonna cure the world, and he fell so low, and is responsible for all these peoples’ death and degradations.

S: Yes.

DK: But he’s not gonna face it because he’s a drug addict. No disrespect to drug addicts. But he thought drugs were going to free humanity, but they just enslaved him. So he’s no better than the heshers in the woods.

S: Right. They’re even better off. I mean, they’re just smoking weed, like they’re gonna go to work the next– Well, if they hadn’t gotten killed– They were gonna go to work the next day, and done whatever they were planning on doing. Whereas Arboria is stuck in his chair. He’s so far-gone and so withered away that he has to depend on others to give him his drugs. What I also found interesting about him was, if we look at the flashback in 1966 when they’re doing that experiment, he didn’t do it!

DK: Yes!

S: He got Barry– He indoctrinated a young, well-to-do person to buy into every word he said. Go into this unknown gunk. Just fuck his mind up. And then he dumps a baby in it, just to see what would happen. Right after his wife is just unceremoniously killed right in front of him.

DK: His wife is killed, and he comes in, and you see him see the body. And then the next shot is him going, “Your mother’s reabsorption into the cycle of life will not be for nothing.” Like it just skirts right past– that’s scary.

S: Yeah, that’s so sociopathic.

DK: And um, and that’s the other thing 1966 was the year LSD was illegalized in California, and Timothy Leary along with his associates tried to form a religion in which taking acid was the sacrament, as an attempt to stop it from being illegalized.

S: (chuckles)

DK: Imagine being alive then! The whole, like “hippies are scary.” I believe it! ‘Cause these are very powerful substances, and you have scientists losing their minds because of it. Society is transforming in ways you don’t understand, and anyone who says they understand it are either wrong or evil.

S: Lying, yes.

DK: Yeah, and Mercurio is a patriarch. And that’s the thing, I think that the villains are always these toxic men who think they’re in charge or should be in charge, and are either just like irresponsible or downright taking advantage of systems.

S: Yeah, exactly, they’re either taking advantage of a system that is already in play– they have Reagan in the film for a reason. Or you have a person like Arboria who’s creating systems to try to usher in a new reality and be the harbinger of some sort of enlightenment. I do find it interesting that his harbinger is a young girl instead of a boy. Usually these patriarchal figures are trying to pass it on to another patriarch, so you can continue that sort of lineage. Which may actually feed into why Barry ends up the way he ends up. Because he gets no respect out of any of this. They don’t really talk about his place in this at all. He’s still just– He comes on in, and he calls him Mercurio. And he won’t even talk to Barry until he refers to him as Dr. Arboria.

DK: Yeah.

S: That power-play is still there, even on his death bed. When he’s the one who’s in captivity just as much as Elena is at that point.

DK: It’s about how systems enslave everyone, including the captors. And how, like, uh, Barry is in charge, and he hates it.

S: (laughs)

DK: He’s repressing his true self which is, “I just want to kill everyone.”

S: At that point, for sure.

DK: Yeah, I’m glad that you caught on to, like, he’s just taken over the facility. You get this beautiful triumphant– The Sentionauts are sent in and take over. Barry is standing there victoriously, having won. But then the next scene is him going downstairs and still being under Mercurio’s foot. His insecurities and everything he hates about his life are what are keeping him miserable. I like that the movie– He’s a multi-dimensional villain where he’s so scary, he’s very gross. But he’s also very pitiable.

S: Yes.

DK: And the flashback reveals this is Arboria’s fault. That this just happened to him. And I was discussing it with my wife. Part of the questions of, like, evil, especially in this movie is: Was it inherently within him, or did he become infected by it from outside? Y’know, he goes to another world, as he says, and he has a theophany from a dark god. He comes back– He has an ego-death and comes back with, like, “I’m just gonna kill everyone.” And that’s scary that you believe him. That’s truly the crusade he’s setting himself on.

S: If you don’t mind, I would love to jump in on something you were just talking about, because that whole ego-death and coming back wanting to kill everybody. It seems, if you were to just watch this in a very flippant kinda, “okay this is what happened kinda way,” then you would just see, yeah we need to have some sort of evil-ness in the character. But what I loved about it actually is… is that not what a true enlightened harbinger of a new age would kinda do? They would look at the problems with society now, and how do you purify. Well if you look at nature, the only purification that exists is eradication. That’s how viruses exist, that’s how parasites exist. That’s how anything that is in their nature to clean for themselves and to terraform basically, is to destroy whatever is there. This is an age-old story as well, I mean even Marvel Comics have done it with characters like Ultron. The whole point is, the only thing that can save humanity is humanity not being there anymore. And although Barry doesn’t have any grandiose speeches of this nature, I do feel that is some sort of driving force behind his actions that we’re not getting to explore.

DK: Yeah, he’s a devil-figure.

S: Yes.

DK: He’s a lieutenant of God and he’s fallen. And ironic part is that God doesn’t even know.

S: Or care.

DK: And that’s what’s scary. ‘Cause Arboria is the father of Elena as is revealed, sorry spoilers. And you brought up her being a girl. I read an analysis of the movie via Gnosticism.

S: Okay, I can see why.

DK: A very ancient religious philosophy, and the bare bones of that to sum up an incredibly ancient and complicated tradition–

S: (chuckles)

DK: –is that the universe is the mind of God. And we all contain a divine spark of God, and when we cultivate that or discover that, we grow closer to God. And a lot of natural philosophers follow that tradition of “the more we learn about the universe, the closer to God we are.” That analysis took Barry’s confrontation with the Divine as, he was knowing the mind of God and it ripped him to pieces. The analysis put Elena as Sophia, who is God’s Wisdom.

S: Mmm!

DK: Because it’s hard to know the mind of God, but when we are acquainted with our wisdom, and Athena fits into that archetype as well. ‘Cause Athena sprouted from the mind of Zeus. And we contain wisdom in ourselves and that’s our connection to the Divine. And Elena is “innocent,” “pure,” I mean she was born in this cult, so she knows nothing else. And her journey is to escape from being trapped, kept away from reality. I love that her journey is from this simulated world into an uncontrolled environment of nature. When she gets out she touches mud and she sees bugs. And she looks up at the universe, and she’s so happy, and it’s because she finally has an unfiltered connection to reality, which Barry was trying to be in control of. Which I think applies to your whole project of like, our connection to Beauty should have no filters. Language is a filter, our words fail–

S: Yes.

DK: –at capturing the beautiful. So just experience it.

S: Exactly. Okay, now I want to dig my claws into that quote that I brought in. ‘Cause I think you’ve set up the stage really well. ‘Cause the quote comes from Plotinus. He was a Hellenistic philosopher who really talked more about metaphysics, oneness, being, the soul, things of this nature. But of course part of the human experience is emotion. And artistry, creativity comes into that as well. So then therefore things like Beauty become a topic of discussion. And I was doing some research, and I was struggling to find a quote that I felt like, “what could I get with this,” and other people were more vague than this movie was, or just didn’t quite touch it the right way. And then I read this one from Plotinus. And, this is it, this is Barry basically, in essence, is what I’ve written out. This quote is [Plotinus] taking a step aside when he’s actually trying to talk about the nature of Beauty. And saying, “okay, if you’re not understanding me yet, how about I explain to you then what the opposite of what I’ve already told you would look like. So what would an ugly soul look like? How would we experience this if we had an ugly soul? What could we perceive?” And it struck me because my stance on this whole project that I’m working on is: in Horror and in discussions of Beauty, both are maligned with this attitude that they are lesser, and that they don’t have a lot to add. So Beauty doesn’t have a lot to add in academic discourse because it takes away from other things. I mentioned this in previous episodes, other topics of discussions in critical theory. It clouds the air basically. And Horror, even in discussions of Beauty, I’ve had a lot of theorists just flippantly say– I had one of them even write down that it would be foolish to try to find a complex Beauty within Horror. Well then color me a fool because I see it very clearly within Horror. Not just normal aesthetics here. We’re not talking, “ooh this red light is really pretty,” we’re talking like what it has to say. And so when I read this description from Plotinus, I felt that this horrid ugly soul that he described was just a human being. Any modern person with their feelings and their desires, and anybody who goes with their drive to sate these instinctual urges. Freely and openly being themselves. I love to challenge these thoughts of him saying it’s ugly and horrid because, in our discussion already about Barry, we’ve already shown that if you were watch the film once you’re going to see a very one-dimensional, creepy, breathing, nasty, erotic character. But if you watch it multiple times, you do see this human side to him and this complexity. And you see how much of his destiny was even taken away from him. Stripped away by somebody even worse than him. So, for me, that’s where the Beauty of the ugliness of humanity lies. Is that our imperfections make us incredibly complex and beautiful creatures. Sometimes we take missteps and go in the wrong direction. Sometimes there is evil and there is true ugliness in the world.