You see, control can never be a means to any practical end. It can never be a means to anything but more control. Like junk.

~ William S. Burroughs

Feel your heartbeat. What is doing that? Squishy cogs in the soft machine circulate healthy blood to the bric-a-brac of your body. Since you don’t actively command the heart to beat, what automated voice speaks from within the delicate sea sponge coiled in your skull?

Who is in control?

That question is asked time and time again in the filmography of Canadian icon David Cronenberg, godfather of the subgenre we call “body horror.” Much has been written about his work, but here I’d like to focus on his various dalliances with that question. I believe his films avoid conclusive answers, instead leaving it up to us to explore, like a juicy cadaver waiting for the autopsy to commence.

The sci-fi creations in early Cronenberg movies exert blunt forms of mind-control. Viruses hijack bodily functions to serve their own procreation. Mutations act like wounds in the genome trying to heal themselves but only spread the derangement. In Shivers (1975), bioengineered parasites propel their hosts into aphrodisiac ecstasy. The infected horde lands somewhere between zombified and body-snatched, their libido absolutely uninhibited. Beyond the invasion of horrible sex-worms, this is meant to invoke the viewer’s revulsion: to live in total submission to the whims of your flesh. The sexual revolution as truly limitless.

In her final speech, Nurse Forsythe describes a dream about an elderly man divulging the erotic power of all flesh. The old man could be Dr. Hobbes, the murderous inventor of the parasite, or he could be an avatar of the parasite’s willpower doing its darndest to entangle Forsythe’s identity with its viral ideology. Have the slugs replaced the minds of the high-rise residents, or have they remained themselves but simply “turned on”? This undefined space invokes our terror at forsaking our carefully constructed identities when our body shakes hands with a virus.

A note on Dr. Hobbes’ fridge reads, “Sex is the invention of a very clever venereal disease.” Pair that with Forsythe’s declaration, “disease is love between two kinds of alien creatures.” Taken together, these Cronenbergian koans express a philosophy that taps into the universal fear of biological coercion. How terrifying it is to lose command of our limbs, our senses, our perceptions of reality—already you can hear the whips of Videodrome snapping in the static between your synapses. A dreaded disease wedges between the mind and body and proposes a threesome. We fear disease not because of destruction but transformation. The blueprints of our wildest nightmares originate in our own nucleic cells, waiting like cosmic vipers to strike.

In Rabid (1977), Cronenberg continues this brand of “venereal horror.” An unconventional life-saving surgery mutates Rose into a horny mosquito. Her fancy new armpit proboscis exsanguinates her victims, who are left with a novel form of rabies. Here, the monster is not disgusting but tantalizing: a seductress whose embrace disguises penetration. The desire to conquer or be conquered muddles the question of who can remain in control during a dangerous mating dance. A victim of circumstance, Rose despairs over her vampiric predicament and ultimately decides to solve the problem herself. In a horrific self-sacrifice, she allows one of her rabid victims to kill her. She takes back control of her story, and the virus vanishes soon after her death.

This theme of tragic suicide recapitulates itself over the course of Cronenberg’s career. In The Dead Zone (1983), burdened with terrible knowledge of the future, Jimmy must attempt an assassination that he knows will be the end of him. In The Fly (1986), the transmogrified Brundlefly puts a gun barrel to his head but is unable to pull the trigger himself. In M. Butterfly (1993), Gallimard becomes the title character using the sharp edge of a mirror. The fetishists in Crash (1996) reach for sexual nirvana nestled in violent death. Cosmopolis (2012) finds its disillusioned antihero allowing his assassin to take the shot at the end. These instances are of course not an avowal of suicide as positive, but rather poses the act as a last-ditch escape from an existence the characters can no longer control and therefore can no longer bear. If losing your identity to the monster is a kind of death, then a merciful exit may be the last resort to restore dignity to the disintegration.

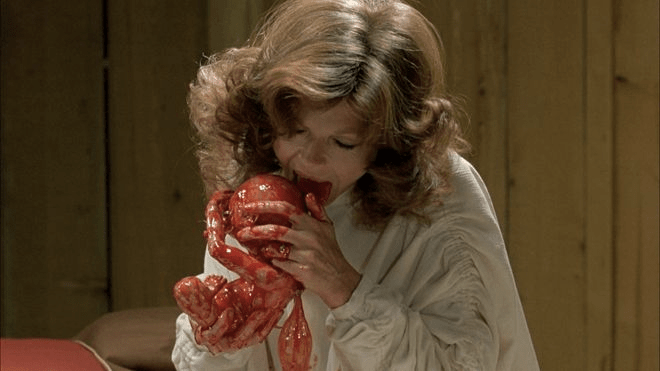

These diseases dissolve the border between our inner and outer selves, a false dichotomy Cronenberg aims to eliminate entirely. In The Brood (1979), a woman’s scorn actually manifests as mutant offspring. Through a radical therapy called “psychoplasmics,” Nola’s lymphatic system produces parthenogenetic fetuses. In a genius twist, the spawn skips the need for sex altogether. Like Dionysus from the thigh of Zeus, these freaks sprout fully formed from Nola’s abdomen. Immaculate conception turned rancid. Eagle-eyed viewers can spot images of the Virgin Mary decorating the wall of Nola’s room—another slam dunk by Carol Spier, Cronenberg’s regular art director.

Here, the mind-control aspect evolves. The children undertake Nola’s subconscious bidding. When her fury sparks, the minions march into the world to savagely hammer the subjects of her hate. Nola doesn’t seem cognizant of their actions, which further mystifies the question of control. As much as her children, Nola is a slave to her own hysteria—the infamous medical label culled from the Greek word for “uterus.” Nola’s very pores become unholy cavities birthing the twisted litter of her trauma. In The Brood, the body becomes a filter for violent thoughts to take literal shape with no one at the wheel. Nola’s rage reaches its zenith when she sets the children upon her own daughter, just to spite Frank. He rescues Candice, but the damage is done. She stares off in traumatized silence.

The final shot of the film ties its premise back into the “virulent horror” Cronenberg has been gestating. After being grabbed by her half-siblings, Candice’s arm bears the marks of their mother’s condition. Did it spread via skin-contact, or is Candice’s lymphatic system regurgitating patterns absorbed from its environment? The cycle of abuse self-perpetuates within the crucible of trauma, leaping from body to body in a mockery of the love we are meant to share. This isn’t a virus from outside the flesh; the wound itself takes control.

Cronenberg later expands this theme of psychological scars as developmental bellwethers. Childhood trauma in Spider (2002) traps its eponymous protagonist in a mental haze, his past as unclear as his future. The past also weighs like an anchor around the hero in A History of Violence (2006). This journey comes to fruition with A Dangerous Method (2011). Cronenberg finally turns the lens on psychologists themselves and their historical effort to grapple with the wounded human psyche. And hopefully control it.

Mind-control moves to the forefront in Scanners (1981). The villainous Darryl Revok forcibly recruits fellow telepaths to his cause of world domination. Again, mental energy directly influences the flesh. Nervous systems sync up for explosive results. In a predictive echo of Videodrome (1983), our hero Vale scans a computer network, hinting that the mechanics of greater consciousness are not limited to the human body. Revok ultimately plans to covertly spread the scanner mutation within the fetuses of expecting mothers. The mutants themselves become the virus, charting an altered course for human history. In the final battle, Vale and Revok use their powers to rip and burn each other’s faces. Telepathy, a usually disembodied superpower, is depicted as firmly rooted in the flesh. The final shot of Scanners poses my thesis literally: Revok’s body possessing Vale’s eyes and voice declaring “We won.”

But who is in control?

Scanners also introduces a theme essential to Cronenberg’s work from here on out: the power of art. One scanner has given up using his abilities and creates sculptures as an outlet for his destructive energy. Standing within a large head he states, “My art makes me sane.” Art helps the artist control reality, a concept central to later works like Naked Lunch (1991), eXistenZ (1999), all the way to Cronenberg’s most recent release Crimes of the Future (2022). And don’t forget that Vaughan, the psychopathic pervert in Crash, recreates celebrity car crashes as twisted performance art. It’s all one journey. It’s all one body.

In Dead Ringers (1988), the twins become famous for inventing a surgical instrument that can modify the human body and in essence control it. With the help of a sculptor played by the star of Scanners, the twins’ next invention signifies their mutual descent into addiction and insanity: an array titled, “gynecological instruments for operating on mutant women.” Though the forces of deterioration doom them, the twins externalize their delusions as freakish art, much like Cronenberg himself. Art replaces suicide as the preferred rebellion against control. But then they do eventually kill themselves with drugs and derangement. Different strokes, I guess.

Additionally, the horror in Dead Ringers comes not only from the personal strife of our stricken twins, but from the layperson’s nightmare of losing trust in the medical system, especially the field dealing with sex organs. When you go under the knife, this esteemed stranger has total dominion over your body. What if that stranger happens to be a drug-addled fiend at the end of his rope?

Who, then, is in control?

Cronenberg’s embodiment of these themes reaches full maturation in his psychotronic masterpiece, Videodrome. Max Renn seeks new extremes of expression to share with his audience. Unfortunately, these extremes are seeking him in return. The titular signal shows Max violent imagery, enticing him to explore further.

Max starts a tryst with Nicki Brand, a call-in psychiatrist, an understanding voice on the radio soothing mental wounds. She introduces Max to sadomasochism, and her face later appears on Max’s mutant TeleRanger commanding his moves. To bring it all home, Nicki is played by rock star Debbie Harry, whose artistic persona has always invaded our screens and ears, soothing and commanding us. That clever venereal disease has already won.

The virulence of this threat is at its most potent; the mere act of witnessing Videodrome infects the mind. The cancerous images quickly subsume reality, and the rest of the film descends into hallucinogenic horror. Inspired by fellow Torontonian Marshall McLuhan, Cronenberg takes the seed of his philosophy—technology as an extension of the human body—and turns it inside out. The protagonist becomes a tool for the forces subjugating the populace via technology. The villains of this film claim to answer my question with gusto: They are in control.

But this sinister plot is Faustian. In the finale, the would-be technocrats find their weapon turned against them. Max is not liberated in his rebellion, but rather becomes a pawn reprogrammed for destruction by warring forces of equal facelessness. The ultimate representation of the terror of losing control. Just like the other suicidal characters, Max blows his head off. But he’s not even the one pulling the trigger, is he?

The gun forcibly fuses to Max’s hand, reducing his body to an instrument of violence. Even his trigger finger is lost in the fleshy lump enveloping his arm. His agency dissolves into the mesh of technology, flesh, and the forces guiding both. The mutations of his arm and his “torso slit” represent literalizations of Max’s psychic reality: his willpower no longer decides the function of his body. It is something else, either malign corporate powers, a tumor spreading across his brain, or a beautiful face on television. Cronenberg warns us, in that moment, we are all Max.

Tiny things hold significant meaning in Videodrome. In the opening scene Max’s watch wakes him: the first indication that technology already guides our lives. Nicki’s masochism advances the clue that our civilization-wide dependence on technology should be redefined as intercourse. We give over our power to various media that dictate every facet of our reality. The conjugal aspect is inseparable. There’s no escaping it.

The new flesh is already here, long may it live.

Max visits “Spectacular Optics” (“Spec Ops” get it?) hoping to find a solution to his worsening visions. Eyeglasses are of course a very simple invention intended to alter reality to better fit our body. Or is it altering our body to better fit reality? Cronenberg finally achieves his goal of transcending that false binary. If the performance art television sets in Crimes of the Future (2022) are to be believed, the body is reality. This gospel takes proper shape in Videodrome and is maintained throughout the rest of Cronenberg’s career. The media has become the massage, and there is a happy ending.

Drink deep, or taste not, the plasma spring!

Beyond this stage of Cronenberg’s career lie his dramas. The bridge takes the form of The Fly, a romantic tragedy cloaked in the trappings of a vomitous monster mash. Seth’s splicing is a complete accident brought on by conjoining mistakes: the personal weakness of his flesh—drunken jealousy—and his machine’s clunky misunderstanding of bioorganic life. Here, the horror is totally abject: no mad scientist, no covert agencies, no philosophy to be found, just a random happenstance of genetic anarchy. Insect politics.

Veronica’s body also comes under threat when she learns that she’s pregnant. She shares in Seth’s horror of an alien presence growing within, hijacking her reproductive system. How prescient that easy access to abortion becomes pivotal to reclaiming control of the body. Veronica’s power to choose becomes her path to survival, something certain forces aim to control or eradicate completely. May their weapons be turned against them.

When Seth discovers his fate, he reacts with gallows humor, cracking wise as his mind rescinds power to the bug emerging within. And then it literally emerges, tearing away his human meat to reveal a gloriously hideous beast. His identity now fully deranged by the urges of his chitinous brain, he becomes a danger to the woman he once loved. This loss of control is tragic. The wound consumes all.

The wound also consumes all in Dead Ringers, when our twins sever their mutual umbilical only to cascade into a shared collapse. Addiction, flagellation, self-loathing, and other usually internal forces are traded between two bodies and one soul. Neither Mantle is in control, and both pay the price of submission.

Now things get really weird.

In Naked Lunch, Bill Lee stands in for author William S. Burroughs. Soon into the story, he is confronted by a giant beetle with a talking asshole (not kidding). This creature declares, “I have instructions for you from Control,” articulating the madness that is about to consume Bill’s life. The bug tells Bill that his wife is secretly working for an enemy agency. He must kill her and make it “real tasty.” Bill obeys, then spends the rest of the film in a drug-induced frenzy, feverishly writing in an attempt to explicate the forces that have steered him down this path of horror.

The artist metabolizes reality into their creative excretions. We the audience consume these excretions and absorb the capacity to battle reality better. Like our gene code learning our environment’s dangers, so it can redesign our defenses. Rather than a frivolous exercise, art becomes essential for evolution. And Lee evolves, much as the works of his creator do. Over his career, Burroughs’ protean poetry evaded all categories in favor of going full Nova. Impossible to detain, unavoidable like a bug in your blood, Uncle Bill whispers sweet and sour nothings into your convulsive ear.

There’s a lot to say about Naked Lunch, but I’ll stick with Bill’s philosophical conclusion: “exterminate all rational thought.” Don’t mistake that for a retreat into solipsism; this statement invites us to communicate in ways that language fails. His cut-up method was partially a way of evading the controlling force of conscious thinking. Art as instinct. He wanted to slice up time and let the future meet the past unhindered by the malignant present. Interact directly with your deepest self, bypassing the word-viruses that corrupt our lingual systems in service of Control—a notion Cronenberg picked up from Burroughs. Or rather, contracted from him.

The relationship between an artist and their creation gets more attention in eXistenZ. Game designer Allegra Geller finds her simulated reality developing quirks outside of her design. She’s open to the process, allowing her invention to discover a life of its own. If technology is an extension of the human corpus, then a work of art is the physical progeny of an artist. Like a child, it carries the DNA of its creator but develops into shapes and behaviors that can vastly differ from the parent’s intentions. In this instance, we must simply let go of control. Cronenberg has come a long way since the hair-lipped “divorce horror” of The Brood.

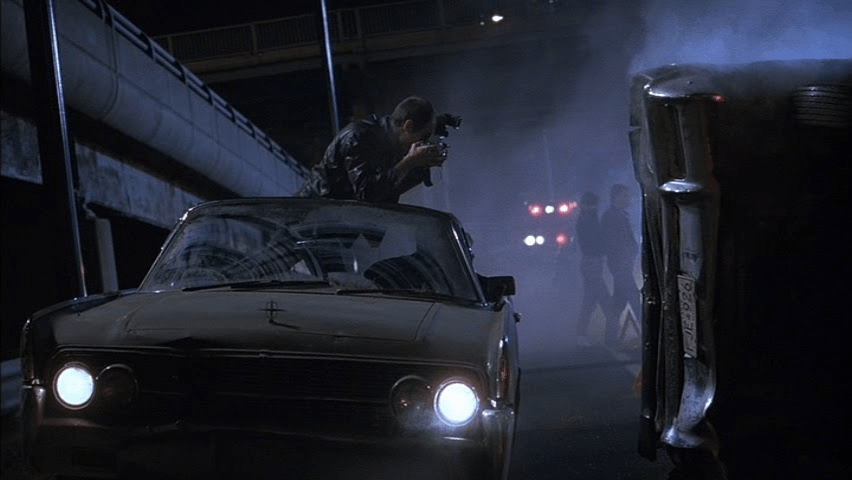

Letting go can also be sexy. Adapting J.G. Ballard’s novel, Crash depicts postmodern disaffection as a default state of mind. The human condition is in constant motion with no true destination. Much like Videodrome, this is a world in which we have no control but gone is the techno-surrealism. Human bodies experience the miracle of mechanized travel in isolated pods of glass and steel, nimbly avoiding any meaningful contact.

Then comes the titular crash: our utter powerlessness made violently apparent in the personalized apocalypse of the auto collision. Our metal carapace either crumples around us in a death-embrace or ejaculates us into space to find purchase as a smear on the unforgiving concrete landscape. And damn is it tasty.

In Crash, those who survive find themselves transformed. The wild abandon of getting thrown from a vehicle veers into erotic territory. Something has taken hold of the collision victims, uncorking latent sexual energy. The dark liberation of Shivers returns but having shed its sci-fi veneer. Pervert/Prophet Vaughan calls the car crash a “benevolent psychopathology that beckons towards us.” As in Scanners and The Fly, the mutation enacts a protocol of spreading itself like a virus; the fetishists trigger the process in others, bolstering their numbers. Again, the wound itself takes control, rewriting the rules of sexuality and society itself.

The hopscotch of human history is two frogs leaping over each other: our environment sparks changes in us, and then we alter our environment to suit our desires. Rinse, wash, repeat. At first glance, the science of body modification appears to be humanity’s rebellion against evolution. We may use our inventions to modify our reality, to control it, but our environment is just as alive and even craftier. In Cronenberg’s much lauded return to body horror, humanity wallows in its victory over nature.

Crimes of the Future finds mutant Saul Tenser spilling his guts for all the world to gawk at. Maladapted humans have evolved beyond pain and slaver over surgical exhibitionism to get as close to the sensation as possible. Injury and pleasure stand on either side of a razor’s edge. Due to his rapidly growing innards, Saul is in constant pain which he and his partner-in-surgery Caprice transmute into art. On the other end, plastic-eating radicals aim to use surgery to reorient human evolution back into control of the world. And in the middle of it all, a National Organ Registry scrambles to categorize the new bodies populating this strange uncharted territory.

Again, the artist battles reality to find productive solutions to the specter of losing control. The question of who controls the growth is brought up many times. In a wondrous twist, it’s revealed that Saul himself is the work of art. With all his novel organs still inside, Saul successfully digests plastic. Nature has chosen him to carry on the next step of evolution. His euphoria is the look of a mutant that has discovered it isn’t an aberration, but an unzipped orifice from which the future freely flows.

The wound takes control back from the knife that made it.

Crimes of the Future goes deeper into the mystery of evolution than any other Cronenberg venture. Rather than finding something horrifying as he’s done so many times before, he found something hopeful. Something is in control. Humans are not always aware of that, which leads to horror, tragedy, and sometimes erotic thrill. But beyond those reactions is an inevitability, a glimpse at the flesh’s infinite power to transform. To transcend its boundaries and redefine reality itself. And we, the lucky living few, are essential participants in that great journey. At second glance, we discover that body modification is a dance with evolution. We alter our reality, but it still gets the last word.

Now comes the final answer to my question: we are all in control. Every human life is fused together by language and technology. Evolution bears us along, but we can choose what we change. The viruses and mutations within these movies threaten the status quo, but redefining boundaries is nature’s way. As mutual inhabitants of the present, we can share control with each other and create reality together. If there’s anything to take away from Cronenberg’s filmography, it’s to remember the immediate fact of our existence: the body. Feel your heartbeat. It’s you. That’s you doing it.

You are in control.